Why Laws Against Child Marriage Are Now Needed More Than Ever

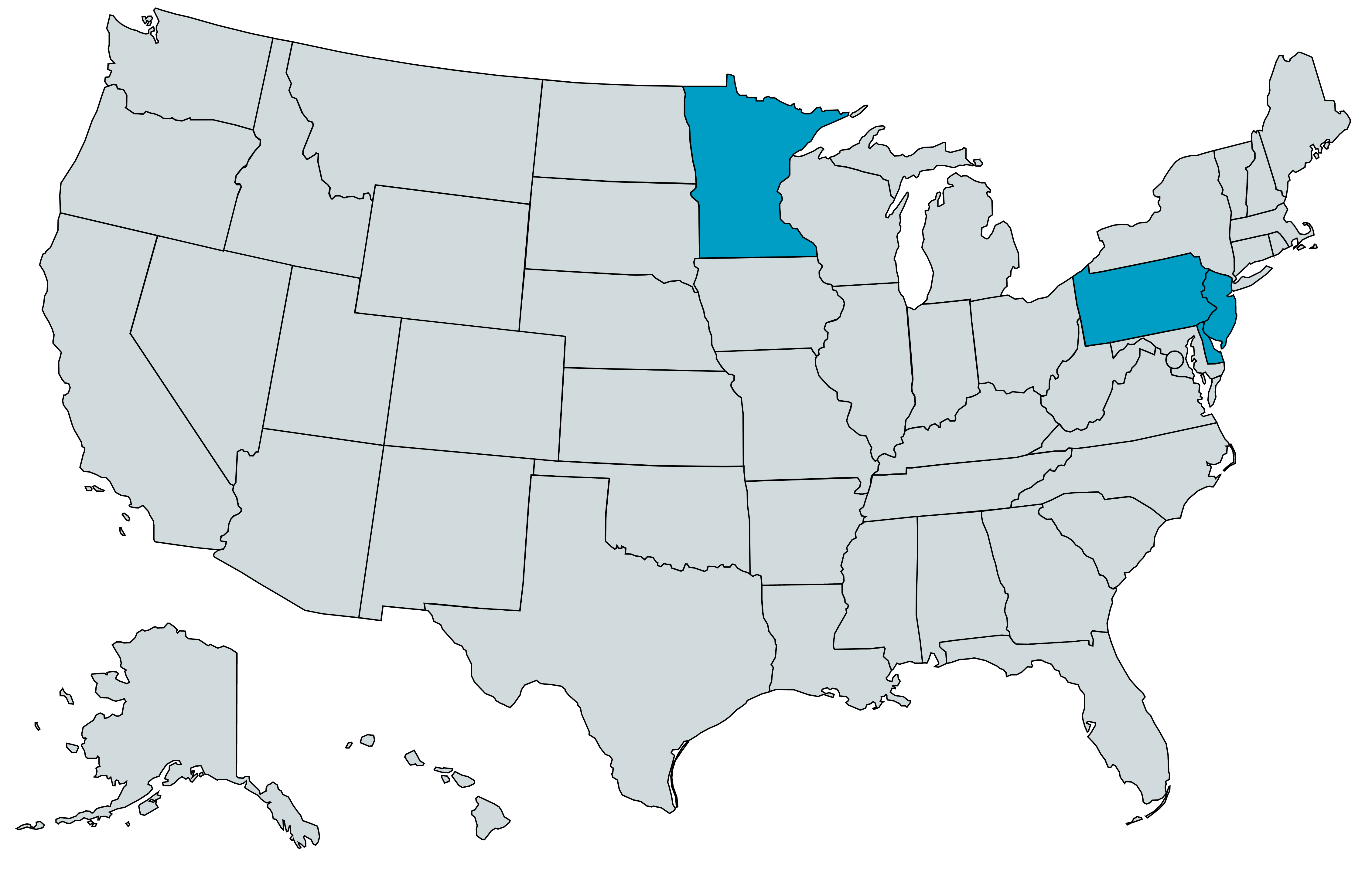

Highlighted in blue are the only states to ban child marriage. We are grateful to New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, and Minnesota for standing up for children's rights.

Both Pennsylvania and Minnesota recently voted unanimously to ban child marriage, becoming the third and fourth states in the nation to take a definitive stand against this child abuse. As a nation, we have a long way to go before we can claim a full victory against child marriage. Amanda Parker, our Senior Director, explains how legal loopholes enable thousands of child marriages across the U.S. every year, why they are failing our children, and why girls are at higher risk from this abuse during the pandemic.

Systematic abuse and exploitation are happening across the nation, and the victims are mostly young girls. Via various legal loopholes, thousands of young girls are being married off every year, in many cases to their rapists. It is estimated that 248,000 minors were married in the U.S. between 2000 and 2010 (source: Unchained at Last).

Many of those child marriages began with statutory rape. The data shows that often when a girl was pregnant or had a baby, and married an adult man, she was unable to legally consent to sex in the state she resides. In each of these instances, the girls’ rapists were handed a marriage license rather than a prison sentence.

Survivors Tell of Lives of Misery, Warn the Public

In most cases, this exploitative practice takes place inside families and hidden from public view. Brave young women who have spoken out about being pushed into marriage as children have shared horror stories. Notably, Sherry Johnson from Tampa tells of being pushed to marry her rapist by her parents when she was only 11 years old and then being trapped in an abusive marriage for many years. At 15 years old, Genevieve was dragged by her mom and abuser through four states until they found a judge in Louisiana who married her to her abuser, a divorced father of two in his 40s.

Sadly, Sherry and Genevieve’s stories are not unique. Globally, underage girls who marry are three times more likely to be victims of domestic violence than those who marry later. A study found that girls who are married as children have much higher rates of mental illness, are more likely to live in poverty as they age, and their own children suffer poor outcomes as well.

A study found that girls who are married as children have much higher rates of mental illness, are more likely to live in poverty as they age, and their own children suffer poor outcomes as well.

Today, amid the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of child marriages is expected to rise, worldwide, and likely in the U.S. as well. In times of crisis, families see child marriage as a way to cope with economic hardships exacerbated by the emergency—marrying a daughter may seem like the only option for reducing the number of mouths to feed.

Child marriage laws vary by state, and 11 states and the District of Columbia do not track such data at all. Several, like California, do not even have a minimum age for marrying, which means a 9-year-old child can get married with just one parent’s consent.

Help end child marriage in the U.S.

Judicial and Parental Consent Don’t Protect Children

Many legislators who defend their states’ current laws allowing minors to marry believe that minors can be protected from entering into harmful marriages by requiring parental or judicial consent. But this approach does not work in practice.

If a child is being forced to marry, the perpetrators are almost always the parents. In these cases, parental consent does nothing to protect the minor from an unwanted marriage.

…a pregnant girl who does not marry is more likely to remain home with her parents and continue her education than if she leaves home to live with the father of her child.

Judicial consent is also not the solution to protecting children from forced marriage. It wrongly puts the onus on minors to reveal to a judge that they are not willingly entering a marriage. This is wrong in and of itself, and made even more so when factoring in that the minor may fear repercussions from family members should they reveal their situation to the judge. Survivors tell us that they would not have outed their parents to judges, even when they realize they are being pressured by their parents into a marriage.

Pregnancy is Not a Good Excuse

Another argument we often hear from legislators defending marriage for minors applies to cases when a girl is pregnant. They argue that having a child born into a marriage is important for the wellbeing of the newborn child. Again, the research shows no evidence for this approach. Instead, we see the opposite—when a child becomes a mother, the outcomes for both her and her children are better if she remains unmarried. It’s easy to understand the benefits to the mother and child because when a pregnant girl does not marry she is more likely to remain home with her parents and continue her education than if she left home to live with the father of her child.

Navigating Religious Beliefs and Cultural Practices

Some legislators are concerned that by voting to deny the marriage of minors, they are infringing on religious beliefs or cultural practices. Child marriage is internationally recognized as a human rights abuse and there is no religion or culture that can justify a human rights abuse, and certainly not an abuse of minors. Further, we have been thrilled to see in the many states where we’ve advocated for an end to child marriage that religious leaders of many faiths have come forward to forcefully fight against the practice too. Often, a legislator will ask about a specific faith community in their district and hear that after being consulted, the leaders from those communities have no issues with, and are often supportive of, efforts to ban marriage before the age of 18.

Emancipation is Not a Solution

In some cases, children are immediately “emancipated” from their parents once they are married. This means that even a 12 or 13-year-old may be considered an adult under the law, no longer protected by their parents or Child Protective Services. Although it does nothing to protect children from the harms of child marriage, being emancipated does mean they can exercise their right to end their marriage with a divorce. But, many then find themselves in a legal no man’s land— without the benefits and recognition that adults in a similar situation receive when rebuilding their lives.

Their divorce rates down the track tell a story of years of misery, with 80 percent of teenage marriages ending in divorce.

On the other hand, without emancipation, as is the case in many U.S. states, a minor can be legally married but is considered too young to be eligible for divorce without the aid of an adult. This restrictive approach gives new meaning to the idea of wedlock. Those children are indeed locked into a marriage with only a difficult route by which to escape. Their divorce rates down the track tell a story of years of misery, with 80 percent of teenage marriages ending in divorce.

For many young people locked in a marriage contract, they must suffer and wait years before they are old enough to legally exit on their own. Either way, emancipated or not, these vulnerable girls lose out.

The Only Way to Protect Children from Abuse

At AHA Foundation, what we demand from states is no less than the exact requirement needed to protect children from this abuse: no minor under the age of 18 should be allowed to get married. We should not ignore those girls here in our own neighborhoods who face exploitation via child marriage. Our state representatives must close the loopholes which have cemented in legislation the second-class status of girls in our community.