“The best cure is prevention. We can’t just continue letting FGM/C happen and reacting to its awful consequences after the fact. We have to do better.” AHA’s anti-FGM/C trainer Oluwadamilola Alabi on her mission to end FGM/C in Chicago North Side

Published 6/7/2022

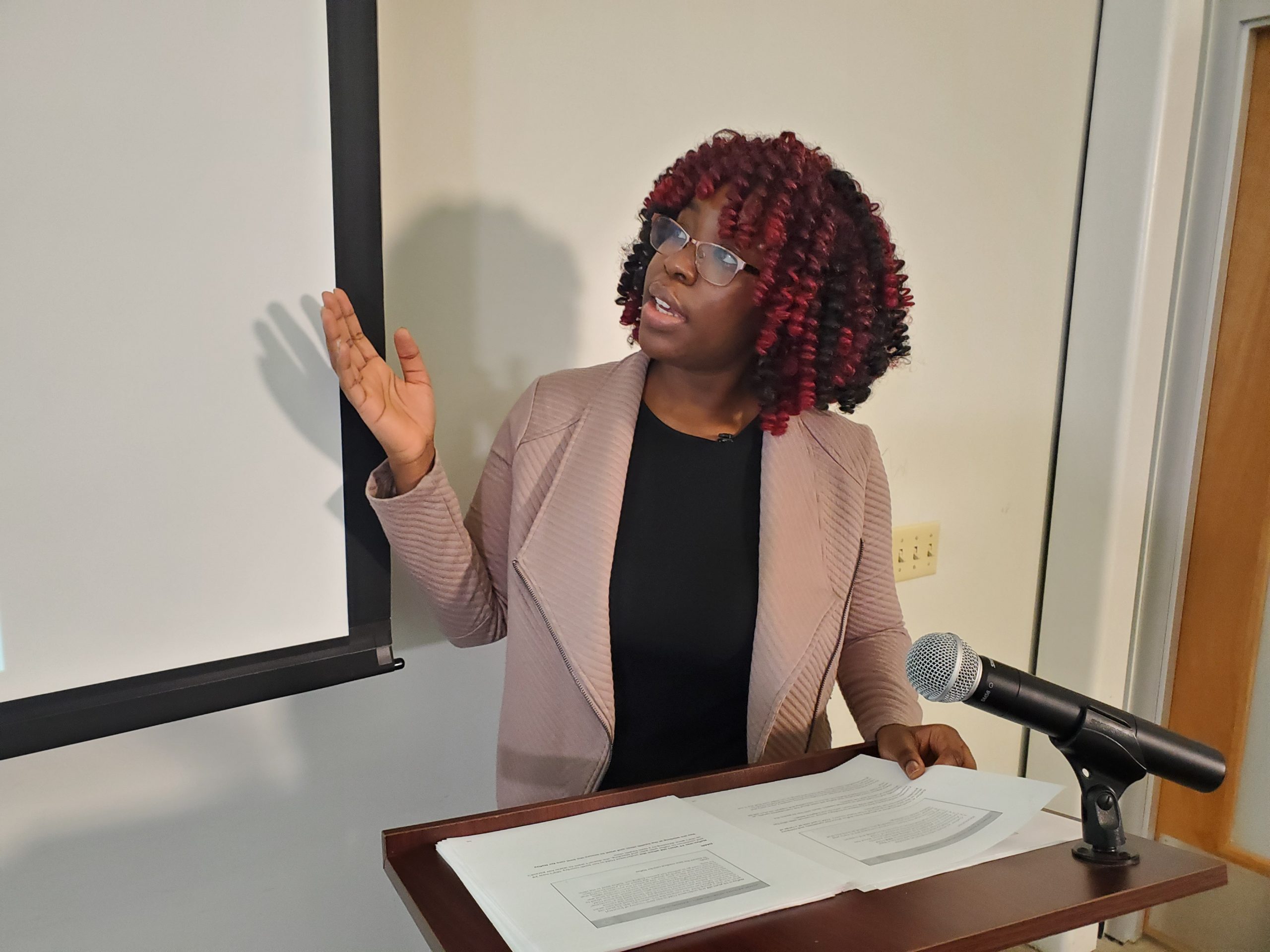

Last year, we shared with you that AHA Foundation had won a 3-year federal grant from the Department of Justice to train frontline professionals about female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C) in Chicago North Side (read more here and here). The program is now in full swing, and we caught up with the project’s coordinator Oluwadamilola (Dami) Alabi to hear all about how it is going and to find out more about her passion for ending this harmful practice.

*The opinions of Oluwadamilola Alabi don’t necessarily reflect those of AHA Foundation*

AHA Foundation: Thanks for speaking with us today, Dami. Could you tell us a little bit about yourself and how you started to work with organizations fighting FGM/C?

Oluwadamilola Alabi: I was born in Nigeria and came to the U.S. when I was 18. I attended Middlesex County College for 2 years and transferred to Rutgers University where I studied Health Administration. I am currently rounding up on my master’s degree in Public Health at Northern Illinois University.

I became concerned about FGM/C when I went to Nigeria for 3 months to do my internship at the University College Hospital in the Department of Public Health. I worked at community clinics where women came for weekly antenatal services. Part of the services we provided were educational talks on various topics, including FGM/C—many of these women had undergone FGM/C at a young age themselves and therefore thought that FGM/C was a normal, natural thing for girls to be subjected to.

FGM is a Reality in the U.S.

Take Action: Demand Zero Tolerance for FGM in the U.S.

AHA Foundation: How did you come to be involved with AHA?

Oluwadamilola Alabi: When I was in college, from which I graduated in 2019, AHA’s then-campus program recruiter saw on LinkedIn that I had done work to combat FGM/C. She reached out to me about the campus program, the Critical Thinking Fellowship (CTF), and I became a fellow, during which time I also attended the CTF summer training in Austin, Texas.

AHA Foundation: Soon after you graduated and completed your fellowship with AHA, you became involved with the WE STOP FGM/C Chicago North Side program. How did that happen? Why are you so committed to combatting FGM/C?

Oluwadamilola Alabi: I became involved in the project because I am passionate about ending FGM/C. When I was in college, I had watched a film about the side effects of FGM/C, which awakened me to the suffering and horror faced by girls and women who undergo and live with it. After watching that film, I was motivated by the fear that such pain could be pointlessly inflicted on any child and I wanted to make a difference.

When I interned in Nigeria, I saw how important it was to educate women on the negative effects of FGM/C. I wanted to ensure that if they had little girls, they would not have to suffer this way. I remember that my mom, who was born and raised in Nigeria, was proud of my work, which just shows that however entrenched a practice is, there are always people willing to challenge it if they believe it is wrong and harmful.

So, when I became involved with AHA, my passion was well-known. I was referred from the campus program to the organizers of the Chicago project and expressed interest in leading the training. I was interviewed and, I’m proud to say, my application was successful. Now I work to end FGM/C in Chicago North Side—there are vulnerable communities here, and I feel honored to be educating them and helping their girls and women.

AHA Foundation: So far, you have helped to conduct 3 training sessions in the Chicago North Side. Tell us about those experiences—who attended, what lessons did you impart, and what difference do you think the training has made for the attendees?

Oluwadamilola Alabi: I was a bit nervous in the beginning because it would be my first time training health care professionals. But the program has been going really well. I have had great experiences at all the trainings because I have had different groups and they all come with different knowledge and ideas. The first training was attended by outreach professionals, the second one by medical professionals, and the third one by mental health professionals.

Despite living and working in this FGM/C-prevalent area, many of [the frontline professionals] had never even heard of FGM/C before. I wasn’t surprised—FGM/C is a topic that isn’t spoken about much. This is why it is so important to break the silence, whether through trainings or by amplifying survivors’ voices. We must speak openly about this harmful practice if we are ever going to end it.

I believe we have imparted a great deal of knowledge about FGM/C to these professionals. Like me before watching that film, they knew very little about it. Despite living and working in this FGM/C-prevalent area, many of them had never even heard of FGM/C before. I wasn’t surprised—FGM/C is a topic that isn’t spoken about much. This is why it is so important to break the silence, whether through trainings or by amplifying survivors’ voices. We must speak openly about this harmful practice if we are ever going to end it. Just as I was enlightened by that film, I hope these professionals were enlightened by the program.

The Chicago program has equipped these professionals with knowledge of the ideology behind FGM/C, its prevalence, how to work with survivors, and how to be advocates against it. Because FGM/C prevalence is high in Chicago North Side, which has a lot of immigrant communities, our training is essential to protect women and girls in that area.

AHA Foundation: What is the one message you want attendees to take from the training sessions?

Oluwadamilola Alabi: The most important thing I want the attendees to know is that FGM/C exists and is a real problem in the United States, and if we do nothing because it does not affect us personally, the practice will continue and more women and girls will suffer horribly.

I am proud of the program because many of the participants take the program seriously and leave the session enthusiastic about taking action to end FGM/C in the area.

AHA Foundation: The program is scheduled to go on for about 3 years. What are the plans for the future of the program, in both the near and the long term?

Oluwadamilola Alabi: The plan is to train more frontline professionals in different fields across Chicago North Side and eventually to replicate the program in Chicago South Side, where there are approximately 1,250 women and girls at risk of FGM/C. We also hope to organize a steering committee to provide a forum to discuss best practices in frontline anti-FGM/C engagement, identify areas of collaboration, and establish relationships with other frontline groups and the community.

AHA Foundation: Have you learned anything yourself from conducting the training?

Oluwadamilola Alabi: I have learnt a lot from the participants, most especially during the case study session. The participants always provide perspectives I have not thought of before. For example, I found out that the Children and Family Services department does not do anything if it receives information about a child at risk of FGM/C. They wait until something has happened before taking any action! This was shocking to me. The best cure is prevention, and that is part of what the Chicago program aims to do. We can’t just continue letting FGM/C happen and reacting to its awful consequences after the fact. We have to do better.

AHA Foundation: Are you optimistic about the future—what difference do you think training these professionals will make in the community?

Oluwadamilola Alabi: I am optimistic about the future. I believe raising awareness about this issue is important. When a wide range of people (frontline professionals, community leaders, parents from practicing communities) are educated about the tools and skills necessary to combat FGM/C, I think we will see real progress.

By the end of the training, there will be more awareness about FGM/C and its negative effects on the health and wellbeing of women and girls and there will be a range of people across different sectors interacting with FGM/C-practicing communities who can educate those communities and assess the level of risk of FGM/C for girls. Most importantly, this will educate the parents. Once parents know the harm FGM/C causes, I have faith that they will protect their children from it.

More on FGM:

- What is FGM?

- Kentucky Survivor Breaks Silence About Genital Mutilation

- “There is a very clear will to end FGM in the U.S., we just need the resources to finish it.” AHA Veteran Amanda Parker on 15 Years of the Fight Against FGM

- Sean Callaghan, U.K. based researcher, finds FGM prevalence in the U.S. 17% higher than CDC latest estimate: “There could be as many as 600,000 women and girls potentially impacted by FGM living in the U.S.”

- AHA Foundation Releases New Legal Guides for FGM Survivors. AHA’s George Zarubin: “To the survivors of FGM, I want to express my admiration for your strength and resilience in the face of true horror. I hope that these guides will help you find justice.”

- Our Reaction to the First Federal FGM Case Dismissal: We Lost a Battle, But Are Resolute in Winning This War