Radicalized As a Teenager, Dr. Manea Now Exposes Dangerous Islamist Tactics Targeting Youth

Dr. Elham Manea is a Yemeni-Swiss Associate Professor specializing in the Middle East, a writer, and a human rights activist. Dr. Manea is a Muslim reformer who researches and speaks out against Islamism – the dangerous ideology facing Western society.

As a part of a series of lectures organized by the Critical Thinking Fellowship, the AHA Foundation Campus Program, Dr. Manea recently spoke at four U.S. campuses about her personal experience of radicalization as a youth in Yemen, her journey out of Islamism, and why it is important to address non-violent extremism – the basis for violent extremism.

Below is an excerpt from her recent book Der Alltägliche Islamismus (translated: Islamism Mainstreamed), published in Kölin, by Kösel-Verlag (Random House Germany), April 2018. In it, Dr. Manea reveals that at 16 her religious beliefs were gradually radicalized one day at a time until her perspective on Islam was no longer the one that her family passed on to her.

This blog is part one of a two-part series featuring Dr. Manea.

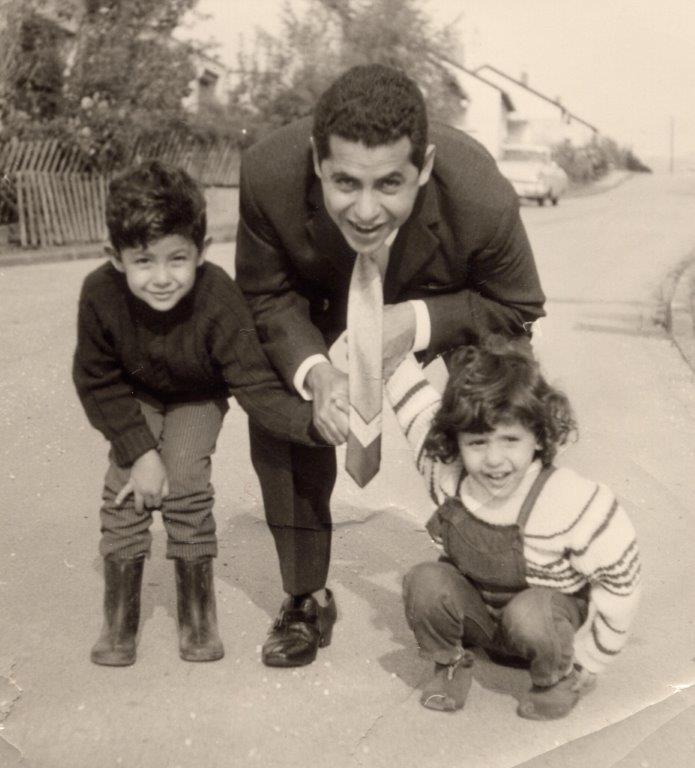

It was in the first months of my return to Yemen that I had my experience with radicalization. My father, a diplomat, was still in Morocco, our home for the past four years. My mother and I came back earlier so I could enroll and start my school year. We stayed temporarily with relatives. Our new house in Hadaa City was not yet ready for us.

In that school, I was radicalized.

Now you have to understand the context here. It was 1982. There were two Yemens at the time. The North, where I come from, run by a conservative tribal military regime, was a satellite state of Saudi Arabia. The South was the only communist regime in the Arabian Peninsula. It was working closely with the Soviet Bloc states and intent on exporting its ‘revolution’ to its Yemeni northern sister and the Gulf States. North Yemen was considered the gate stopping the tide of the communist South. To counter the communist ideology, Saudi Arabia supported the northern regime using an established method at the time; it exported its line of Salafi Islam, a harsh and uncompromising interpretation of a fundamentalist movement created in the 18th century.

“They taught us religion. It was not tolerance that we learned from them.”

Religion was considered the antidote to the communist ideology. But it was not just any religion that was used. It was an extremist version. The religious curriculum of the country’s formal schools was changed in the late 1970s, an outcome of systematic efforts by Muslim Brotherhood and Salafi functionaries at the Education Ministry. Instead of the earlier one hour a week of ethics, now students spent eight hours with Salafi readings on religion. With the support of Saudi Arabia, a parallel religious educational system was created.

Thousands of institutions for both genders, called the Scientific Institutions, were created to indoctrinate young Yemenis. Mosques were erected with imams preaching this Sunni line of Islam, slowly changing the confessional demographic in the North. Young men were urged to join the holy jihad against the Soviet infidels in Afghanistan. Thousands were recruited. The Muslim Brothers were working hand in hand with the Salafis of Yemen, with the Kingdom generously supporting both. At that time there was a clear alliance between the Yemeni state and the Islamists; a convenient marriage that continued despite some hiccups until the first decade of the 21st century.

That marriage was reflected in my school. Our teachers were Egyptians and Syrians. Many of them were members of the Muslim Brotherhood who had fled their own countries. They taught us religion. It was not tolerance that we learned from them.

Tellingly, young Yemeni Salafists and members of the Muslim Brotherhood were allowed to preach openly in the school. This is how I came to be involved with them. Every day, a circle of young students, with a charismatic leader, whom I will call Nadia, would sit in a circle in the middle of the school yard, during the school’s long lunch break. I got curious, asked a classmate about them, and was told they were pious religious sisters talking about religion. So I sat with them and was embraced with open arms.

At the beginning, Nadia’s message was one of kindness, of thoughts on how to be a good Muslim. You should smile at others. If you see something that could harm others in the middle of the road, you should pick it up. When you are greeted, answer with a better and longer greeting. Be a good neighbor and a good daughter. When you do, you will be rewarded generously in the afterlife – a good deed is always rewarded sevenfold.

“My mother’s way of Islam was simple, very spiritual in nature despite its traditional clout. You pray, fast, and love God – and God will love you back.”

Of course, you should be a good Muslim. Apparently, Muslim societies, including Yemen, were not really Islamic. They were practicing a corrupted version of Islam. To understand what I mean here, we have to go back to the true way of Islam: a way that is detailed, heavily structured, and fully laden with rituals. Now we were told about the mercy of God. Nadia explained to us that the moment we enter into Islam, all our sins will be washed away. Islam erases all that you have done during your pre-Islamic way of life. Whatever wrongs we have done, will be forgiven. We will be born-again Muslims. But first we have to follow the right way of Islam.

The right way of Islam was introduced to me in small booklets, given to me for free.

They taught me how to pray: not only the five prayers, but also what you say in them, and which prayers you can add to them – several, it turned out. It is also how you fold your hands when you pray and how you position your feet when prostrating yourself. Later I learned about the sectarian significance of the hand folding: if you pray with your hands stretched out at your sides, you will be following the Shiite tradition of prayer – not one they advocated.

These booklets told me what prayer to say when I would leave the house, travel or enter the bathroom. Which foot to use when entering the bathroom – the left – and which hand to eat with – the right. Satan likes to eat with his left hand so we should not emulate him. You use your left hand or foot when you do things that are not clean – what you do in the bathroom is not clean.

They even specified how to relieve yourself in the bathroom. You should lean to the left, as there is significant scientific evidence of the health benefits of the Prophet’s way of relieving himself. It never occurred to me to inquire about these health benefits – they knew better, of course. Plucking your hair from your body or face, using nail polish: all of these were frowned upon. Naturally, you should not try to emulate the other sex in their behaviour or clothing; trousers were not welcomed.

I told you that, up until now, I mainly knew religion through my mother and my private tutor, Sheikh Al Shawadfy. My religion classes in the other schools were simply boring, with their repetitiveness and their frowning God. My mother’s way of Islam was simple, very spiritual in nature despite its traditional clout. You pray, fast, and love God – and God will love you back.

In Rabat [Morocco], I was lucky to be taught by the Egyptian Sheikh Al Shawdfy. Four years of weekly private lessons. My father, the agnostic humanist, heard about him – he taught Arabic language and religion to Prince Hisham, the nephew of King Hasan. So my father contacted him and tried to convince him to teach my brother and me. The sheikh refused. He did not believe in paid private lessons. My father persisted and pleaded with him that he should meet us first and decide for himself whether teaching us was worth the trouble. The sheikh finally agreed to meet us and indeed changed his mind. Yet he refused to be paid for the classes. I remain grateful to him for his devotion.

I always respected him, as a man of integrity and great knowledge. His way of teaching was focused on the richness of the Arabic language, giving me a strong basis in Arabic poetry during its various historical phases. He taught us religion but not in the ritualistic way I learned in Yemen. It was about the basics but with a general understanding of Quranic stories and their morals.

It would be an exaggeration to say he was liberal. I still remember the expression on his face when he heard about a book I was reading, one given me by my father: The Days, the memoir of the famous Egyptian intellectual, Taha Husain (1889-1973). Husain was a critical thinker, strongly opposed to the Al Azhar religious institution; in his writing he suggested that the Qur’an should not be taken as an objective source of history.

The look on his face was clearly one of disapproval. But he did not say a word against Taha Husain. He merely suggested that I might benefit more from reading other books. Despite his disapproval, he did not talk badly about him. Just like my mother, his approach to religion was certainly different from that of the missionary group at my school in Sana’a.

And yet, despite this background, the missionary sessions fascinated me. There was something very reassuring about them. For a teenage girl, searching for her identity, the message was mesmerizing, and at the beginning I embraced it wholeheartedly.

“And the belief – that strong belief that you are in good hands, that God is always on your side – was intoxicating.”

You see, with them, I did not have to choose. The choice they gave me was clear, undivided and not confusing: you are Muslim. One. That is your identity. You do not have to choose between two nationalities. Religion is your identity. And identity was very important in this whole context.

‘Who am I, grandmother?’ I asked that repeatedly in my first Arabic novel, Echo of Pain.

Who am I indeed?

Half, half. That is how it felt at that time. I was called half caste, muwallada: an expression in North Yemen preserved for those of mixed blood. Born in Egypt, to a mother of mixed Egyptian-Yemeni origins, I was never allowed to forget that I did not really belong. In Yemen, I was the tall Egyptian, and in Egypt, I was the Yemeni. I also did not know how to sort out all of these other countries and their memories: Germany, Iran and most importantly, Morocco. Where do they fit in me? Too many places, too many nationalities, and too many identities. Together they made me the person I am today. Whole. But at that time, it was very confusing. Who am I, indeed, grandmother? With Nadia and her group, I did not have to choose. It was simple. I am a Muslim, full stop. This is the identity, total and complete.

The changes in me were gradual. It started with everyday language. Instead of greeting others with ‘good morning’ or ‘good evening’, as we used to, I began using only what they called the salute of Islam: assalamu alaikum, peace be upon you. Later I would learn that this salute is only reserved for Muslims – real Muslims. “Do not use it with non-Muslims,” I was told. “We are not at peace with them. If you say it to them, you will commit hypocrisy”.

My days took on a rigid religious structure, starting with the dawn prayer and moving to the evening prayer. Part of the night was dedicated to worship, and reciting from the Quran was a must. It was strict, but simple and clear. A way of life far from the one I had had in Morocco. The rituals were comforting. Your whole day was tightly organized. And the belief – that strong belief that you are in good hands, that God is always on your side – was intoxicating.

One incident illustrates the strength of the belief I’m describing here. In 1982, North Yemen had a devastating earthquake. It was a strong one, measuring 6.2 on the Richter scale, and 2,800 people died. I was in school when it happened and it was frightening. After the first earthquake, many people decided to stay outside their buildings and homes, fearing aftershocks. Not me. I went to my uncle’s apartment, where I was staying at the time, took out my prayer carpet, and kept praying. I felt pity for those poor souls, fearing death that way. I was sure that if death came now, I would go straight to heaven. Why should I be afraid? I took up the true religion, and my sins were already erased. That is how I felt.

I was told that from now on, I would have to call the members of the circle ‘sisters’. We were ‘sisters in God’. We did not see the ‘brothers’. But the men who belonged to the group, I was told, should also be called ‘brothers.’ We, those who believed, were brothers and sisters, united in our belief. It was our family now, a bond that must transcend my blood relations. We should follow the lives of Mohammad, the Prophet of Islam, and his companions. They too were brothers and sisters working together against the infidels of the time. They had to sacrifice their lives, families and belongings for the Islamic cause. They should be our role models.

“I had to aspire to be a better Muslim – all the time – and the more I did, the more I was required to do.”

“You have to wear the hijab,” they told me. “Hell will be filled with women hanged by their hair because of the way they seduced men with their beauty,” and “You will make these men commit sins by showing your feminine side.” Guilt was a feeling I had constantly during this period. I had to aspire to be a better Muslim – all the time – and the more I did, the more I was required to do.

They did not ask me to wear the sharshaf [black clothing worn by Yemeni women that covers their entire face and body]. Even the Salafis do not ask Yemeni women to wear the traditional sharshaf. They want women to wear the Saudi niqab – their uniform. Similarly, the Muslim Brothers group insisted on us wearing their distinctive uniform at the time: a long headscarf that covers the whole body, leaving the face and hands free. I was not willing to take on that uniform. But I complied nevertheless, covering my head with a hijab and wearing a long coat over my body. I hated it despite my love of God. It suffocated me. But I did it. If this was the price for God’s love, how could I object?

But their message grew to be troubling and questions began to stir in my mind. I was told all those around me, including my practicing loving mother, were living in jahiliyya – the state of ignorance and false belief that prevailed before the time of Islam. I was just like the companions of Mohammed: if my family asked me to forsake my new belief, I would have to renounce my parents and their society.

I started to feel uncomfortable but said nothing.

I was told that everything that made up civilization was forbidden: painting, sculpture, art, music, poetry, and philosophy. All of these were part of jahiliyya and prohibited by Islam.

“I complied… covering my head with a hijab and wearing a long coat over my body…. It suffocated me… If this was the price for God’s love, how could I object?”

I grew up surrounded by paintings, sculpture, and music. I recited poetry and read books that glorified philosophers. Why should beauty, life and wisdom be forbidden?

The more I embraced their message, the more I was drawn away from my family and most importantly from my father. When he finally arrived from Morocco he realized that something had gone wrong. He met a changed daughter. The outgoing, laughing, inquisitive daughter he knew was now very subdued, quiet and covered. She was trying, kindly, to convince him to follow the path of Islam. Something had happened in his absence and he did not like it.

He objected to my wearing the hijab. “Your hair is beautiful, why do you cover it?” He objected to my narration of Islam and the world. He kept talking to me, telling me that it is normal for a teenager to seek answers and sometimes religion might seem to be the answer. But I should be careful about the type of religion I was embracing. I started to get angry and spoke louder. “This is Islam,” I insisted. “It is fundamentalism you are embracing,” he would reply, always calmly. Somehow, he knew he should remain calm in the face of my anger.

I think at this stage I began to tear at the shrouds of my hypnotization. You see, the alarm bells I heard when they said my mother was involved in jahiliyya grew louder when they switched to target my father. He was no longer my father, they said; he was an enemy of Islam.

“If my family asked me to forsake my new belief, I would have to renounce my parents and their society.”

When I complained to my group about our arguments, they repeated the message about the companions of Mohammed and how sometimes they had to fight their own family members, even on the battlefield. Some of them had to go so far as to kill their own fathers and sons for the love of Islam. That is what the companions did; that is how strong their belief was.

By this time, our meetings were no longer in the school, but in the homes of young members of the movement. Regular sessions. Older women were talking to us now. The message became political, in essence sanctioning violence. It is jihad, they said, and it is meant to spread Islam.

“The more I embraced their message, the more I was drawn away from my family…”

They said that killing was OK. I was given a booklet about the life of Khaled Eslamboli, the army officer who planned the assassination of Egyptian President Anwar Al-Sadat in 1981. Eslamboli was called a “hero of Islam.” Sadat, they said, was a pharaoh who made peace with Israel, who worked with Jews intent on destroying Islam. He deserved to die.

Short booklets served the purpose of providing clear and direct messages. In addition to the ones that preached about praying, women’s behaviour, and the beauty of martyrdom, there were also short versions of important books written by radical Islamist thinkers such as Hasan al Bana, Sayyid Qutb and Abul A’la Mawdudi. But one book was given to me in its entirety: Milestones by Sayyid Qutb, considered the manual for violent jihadist Islamists. He kept repeating in his book that all Muslim societies are living in ignorance, and to create the Islamic state, it is OK to fight these ignorant Muslims.

“The message became political, in essence sanctioning violence.”

In all the booklets, literature and preaching sessions, hatred of the Jews was a common thread. Pure hatred. And please note that the core of that hatred was not the state of Israel, although it was always mentioned as a target for ultimate destruction. No. It was the Jews themselves, their Jewishness.

God had cursed the Jews and turned them into pigs and monkeys. Quranic verses were used to support that argument. Accordingly, today Jews were the descendants of these pigs and apes. That hatred was laden with an epochal religious doomsday dichotomy: good and evil. At the end of time, when the final Islamic victory comes, even the trees and the stones will tell on the Jews, calling on Muslims to come and kill the Jews hiding behind them. That saying of Mohammad was used here to support this belief. Hatred. Jews are sub-humans conspiring with other forces against Islam. Jews, communists, and crusaders: these are the forces trying to destroy Islam. While communists were heavily denounced for their atheism, Jews had a special place in the dichotomy of us versus them: the forces of evil par excellence. The taste of that hatred was bitter. I did not like it.

‘War is deception.’ Only when I started to research Islamism did I realize the implications of this saying, attributed to Mohammad, which was constantly repeated in our religious sessions. They told us detailed stories of early companions of the Prophet. They converted to Islam, and Mohammad told them not to reveal their conversion, as a means to deceive their own people during the time of confrontation between belief and disbelief. War is deception, they said, and it is OK to deceive the infidels in order to raise the banner of Islam.

It was not just the militant dimension of their message that finally made me realize that something was fundamentally wrong with this group. It was the gender aspect. The moment of recognition came in an afternoon session led by an older woman I will call Bushra. She was telling us about the importance of obeying our husbands. For women, the way to heaven is through fulfilling their marital duties. The Prophet once said if it was not for the fact that only God should be worshiped, he would have suggested that wives prostrate themselves to their husbands, as they would when praying. But it was what Bushra said next that broke this camel’s back. She repeated a saying attributed to the Prophet about a woman who ignored her husband’s order not to visit her sick father. I was told the Prophet said, “the angels are cursing her now, for she defied her husband’s order.”

“It was not just the militant dimension of their message that finally made me realize that something was fundamentally wrong with this group. It was the gender aspect.”

That afternoon, I left our meeting knowing I would never return. Who should be cursed here, I asked myself. The woman who wants to visit her sick father or this bloody husband, who has no mercy in his heart?

Remember my mother? She became mentally ill because of patriarchal notions about how to treat a girl and later a woman. I was too young to articulate that in words or to make the connections. But as I heard Bushra utter that sentence, the anger inside of me tipped the scale of my doubts and settled my struggle. I knew then that the God this group worshiped would not bring me salvation.

With a sigh of relief my father witnessed the end of my short flirtation with Islamism. As the first sign of the end, I took off my headscarf.

“I knew then that the God this group worshiped would not bring me salvation.”

But I was lucky. I was raised in a context that provided me with the tools to question everything I was told, not to take things at face value. Others are not so lucky and remain entangled in a web of radicalism.

The opinions stated above are those of Dr. Elham Manea and do not necessarily represent the views of the AHA Foundation.

Stay tuned for the second blog in a two-blog series from Dr. Manea sharing her fight against Islamism.