Lessons from the Shafia Mass Honor Killing

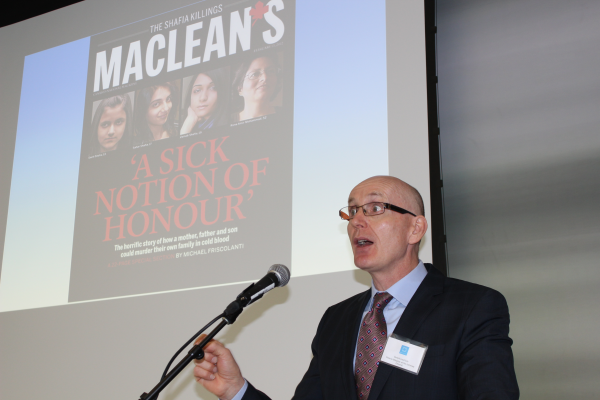

Gerard Laarhuis, Assistant Crown Attorney, Ontario, discusses the mass honor killing of four members of the Shafia family at the AHA Foundation's Third Annual Conference on Honor Violence, Forced Marriage, and Female Genital Mutilation.

During the AHA Foundation’s Third Annual Conference on Honor Violence, Forced Marriage, and Female Genital Mutilation, held in December of 2013 in New York City, an impressive host of speakers engaged a large crowd of activists, teachers, doctors, academics, and lawyers. The keynote presentation was “Profile of A (Mass) Honor Killing: The Shafia Family Murders,” given by Gerard Laarhuis, Assistant Crown Attorney in Ontario, Canada.

Laarhuis led the Shafia murder case, the first successful prosecution of a multi-victim honor killing in North America. In 2009, Mohammed and Tooba Shafia, along with their son Hamed, conspired to and killed their three daughters Zainab (19), Sahar (17), and Geeti (13), as well as Mohammed’s polygamist first wife, Rona (50). (The Shafias have three other living children.)

During Laarhuis’ presentation, one of the most heartbreaking aspects of this case was the fear and oppression the Shafia children lived under in the months leading up to their deaths, and presumably, for much of their lives. Rona was treated as a servant and second-class citizen in the family, even though she raised the children as her own. In her diary and in messages to family members, she repeatedly mentioned fearing for her life at the hands of Tooba and Mohamed. She sent photos of herself to her family back home because the photos of her that had been around the house kept disappearing; she thought she might be killed and wanted there to be a record of her existence.

Zainab, the oldest, had run away to a shelter once before due to the abuse at home. Sahar had coached her boyfriend to pretend he was dating one of her friends if her brother Hamed were to catch them together. Geeti reported that her father said he was going to kill her and her sisters on many occasions. It is hard to imagine the extreme punishment these women faced at the hands of not only their parents, but their brother too. In the ensuing investigation of the murders, the other three children indicated that they knew their parents were responsible for the deaths of their family members and knew the motivation for the homicides. There was no denying that this was an honor-based crime and that the Shafias wholeheartedly believed it an act necessitated by the behavior of the victims.

Laarhuis’ presentation and the reporting around the case have underscored the need for comprehensive training and guidelines for authorities dealing with potential honor violence situations. Tragically, there were many signs that Zainab, Sahar, and Geeti were in a dangerous situation well before their murders. The sisters told authorities that they feared the violence of their parents and brother. Sahar and Geeti began failing in school, losing extreme amounts of weight, acting out, and dressing in a manner that was deemed “promiscuous.” Zainab ran away and briefly married her boyfriend in an attempt to get out of her father’s home. Her family forced her to immediately annul the marriage.

Despite evidence of abuse and reports to the proper authorities, it is in fact very common for victims of honor violence to recant their accounts under pressure from their families. In the case of the Shafia sisters, at one point, the authorities interviewed them in front of their parents, which, unsurprisingly, caused them to stop talking. Soon after, Sahar attempted suicide and was interviewed by a caseworker. She initially described how terrified she was of her brother, but when she was informed that her allegations would be reported to her parents, she stopped cooperating with the investigation. These multiple warnings that the Shafia girls were being abused and threatened went unaddressed, and a few months later, they were dead.

In January 2012, Mohammed, Tooba, and Hamed Shafia were convicted of the four murders and sentenced to life in prison. Their case made headlines throughout Canada and the rest of the world. This case illustrates the importance of education, awareness, and training for authorities who may interact with victims of honor violence. There is no excuse for not intervening sooner in their case, when there were numerous signs that things in the Shafia household were heading toward a dangerous and violent end. If we are able to recognize and address honor violence before it escalates to an honor killing, we may be able to save the lives of women and girls like the Shafias.

The training of law enforcement professionals, child protective services and other service providers is a top priority for the AHA Foundation. We have already trained thousands of professionals on the best practices for identifying and handling cases of honor violence. Armed with this knowledge, these professionals are better equipped to appropriately address situations of honor violence, before it is too late.