Hila’s Story: Choosing a Life of Hiding to Escape Honor Violence

By *Hila

In the 70s, my parents emigrated from Yemen to the U.S. While they did many things to assimilate to life in the U.S., breaking tradition from arranging marriages for their children was not one of them. It was clear that my sisters and I (unlike our brothers) would not have a choice in who our husbands would be.

In 2000, when I was 18, my sister and I left our family, to avoid forced marriages and to escape the traditions of misogyny in our culture. We knew that our leaving would be a huge stain to the ‘honor’ of the family, making honor violence a very real threat and justifiable within the eyes of the community to remove our family’s shame at having daughters who caused such a huge disgrace.

Initially, we sought assistance from authorities to change our identities, but help turned out to be fruitless. At that time, there was even less awareness of the gravity of these situations among professionals than there is today.

The only help we could find at the time that was even remotely relevant to our situation was via a domestic abuse agency. From what I remember, they didn’t really know what to do with us. It was new territory for them. Name changes were the easy part; what we needed most were new social security numbers. I remember the domestic abuse agency sending our paperwork to some office in DC and our request getting rejected. There was no interview, no application, no process.

We eventually found other means to change our identities so we could start working and begin new lives.

The change in identities was crucial to moving forward, though at the same time it caused further challenges for me. It was always in my plans to attend college and I had worked hard towards this goal. Unfortunately, I found that after separating my new identity from my old, it was too difficult to prove that I had taken the necessary steps to be admitted to university, which discouraged me from pursuing this goal.

Some years after we left, I came across the guidebook for the UK’s Forced Marriage Unit (FMU). It blew my mind. I was shocked at how thorough and sensitive to cultural practices the training guides were. For example, the instructions in the guidebook clearly state to never approach a potential victim’s family without her/his consent. This is one of the reasons I think many women are reluctant to seek help or approach authorities. The fear that it will come back to their families is too great a risk as the consequences can be severe, even deadly.

Here in the U.S., we need a local version of the FMU, especially with a hotline that is safe to call anonymously. I think potential victims need to be reassured that approaching authorities won’t immediately backfire on them, and they need appropriate services to continue supporting them after they have reached out for help (similar to what the organization Karma Nirvana does in the UK).

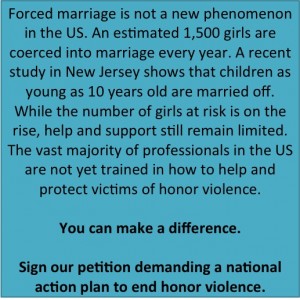

While there are not many resources for help that I am aware of, thankfully more exist today than when my sister and I left our family. Just the mere fact that I could refer women and girls facing similar situations to organizations like the AHA Foundation, Unchained at Last, and/or the Tahirih Justice Center represents huge progress. Even given the growing recognition of honor violence, there remain many women who remain locked in a cycle of abuse, coercion and fear, unable to reach out without putting themselves further at risk.

It may be difficult for some to understand, but I don’t want to demonize my parents.

Their actions would be no different than most in our community. I believe they tried to do what was best given the challenges they faced as recent immigrants within a culture of significantly different values. I was however, and still am, frustrated and angered by the abusive practices carried out in the name of tradition, culture, and honor. Education and awareness are still very much needed in my community to ensure women and girls are safe from the misogyny my sister and I fled.

*Identifying details have been changed.