Founding Member of the U.K.’s National FGM Centre Uses Her Expertise to Help Girls in the U.S.

Lisa Brett, AHA Foundation Senior Consultant

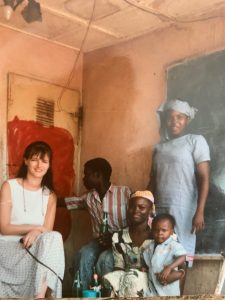

Lisa Brett is a Senior Consultant for AHA Foundation. She previously worked in manufacturing before joining the Voluntary Service Overseas in 1989 to become a teacher in Nigeria, where she first learned about the practice of female genital mutilation. After returning to England, Lisa worked for a charity called Victim Support and became involved in local politics. She was later elected to the U.K.’s Local Government Association and became Deputy Chair of the Safer, Stronger Communities Board where she helped found the National FGM Centre in 2014 and chaired their advisory board. Lisa moved to Washington, D.C. in 2017 and currently supports AHA Foundation’s activities in tackling honor-based violence.

AHA Foundation: You studied electronics and worked in manufacturing early in your career. What prompted you to turn to advocacy and fighting to end female genital mutilation (FGM) in the U.K. and globally?

Lisa: I joined the U.K.’s Voluntary Services Overseas program to become a teacher of introductory technology in Nigeria. It was there I first heard of the practice of FGM from my students from Northern Nigeria. At the time, I did not intend to leave my career in electronics, but having taken several years off to teach and start a family, electronics sort of left me behind! Helping to tackle the abuse of women seemed a natural calling for me after working in Nigeria and later Honduras.

AHA Foundation: How has the landscape of the fight against FGM changed since you first learned of FGM in 1989? Are U.K. citizens more aware of this practice?

Lisa: Awareness of FGM as a form of child abuse has increased enormously since 1989. International organizations and governments have started to take action; they began to introduce and change laws, and provide education in practicing communities about the serious risks to health that FGM presents. But there is still a great deal more to be done.

“I strongly believe that it is early intervention to prevent FGM from occurring – rather than the prosecution of perpetrators – that should be our main goal, and unfortunately I see little evidence of this being the focus of attention in the U.S.”

AHA Foundation: In 2012, you were elected to the U.K.’s Local Government Association, a Westminster lobby group. How does your experience in politics help you in your work to end FGM?

Lisa: I think I have a strong grasp of the constraints politicians face, particularly budgetary constraints. I also recognize that, even with the best of intentions, requests can rarely be met immediately. However, that doesn’t mean that citizens cannot politely pressure their representatives to make a difference!

“I am saddened at the lack of education, media coverage, and wider political support surrounding FGM in the U.S. compared to the U.K.”

AHA Foundation: You moved to the U.S. in 2017. Do you see a difference in awareness and how anti-FGM laws are prioritized by legislators between the two different countries? As you learned more about the movement against FGM in the U.S., were you surprised by any of its aspects?

Lisa: I am saddened at the lack of education, media coverage, and wider political support surrounding FGM in the U.S. compared to the U.K.

I remain horrified that many states haven’t put laws in place against this practice. Legislation is essential to supporting the prevention of FGM. Our ideal model legislation not only criminalizes FGM, but requires education and outreach to at-risk communities across the state. By requiring outreach and education, we can ensure at-risk women and girls are aware that this practice is illegal, and has no health benefits. I strongly believe that it is early intervention to prevent FGM from occurring – rather than the prosecution of perpetrators – that should be our main goal, and unfortunately I see little evidence of this being the focus of attention in the U.S.

For example, in the U.K., the National FGM Centre is largely funded by the Department for Education, whereas in the U.S. there is just a tiny amount of funding available from the Department of Health and the Justice Department to tackle the issue. The lack of federal and state funding available in the U.S. to combat FGM is really very surprising when I compare it to the U.K.

AHA Foundation: What successful approaches have been used to protect girls in Europe from FGM that could work in the U.S.? Are they government mandated or have they resulted from advocacy work, or both?

Lisa: Child protection laws in the U.K. have been strengthened to specifically highlight FGM as a form of child abuse. This was a huge step forward. Finally, we recognized FGM for what it is – a child abuse taking place in our country. Seen in that light, it was even more evident we had to do something immediately to start preventing this abuse.

FGM is now subject to mandatory reporting from teachers and health professionals. This is not the case in the U.S., and this change has led to better trainings in grade schools, teaching hospitals, and with social workers too. In addition, elementary and middle schools are very open to raising awareness among pupils in areas where FGM is known to be of high prevalence.

“I believe failing to challenge oppression is the most racist and misogynistic action a politician can take.”

AHA Foundation: FGM advocates and experts fighting the issue globally often warn that the U.S., when compared to other developed countries, is behind in recognizing and teaching about harmful cultural practices such as honor violence and FGM. Can the U.S. adopt some policies from the U.K.? If so, which ones specifically would you recommend?

Lisa: I think many Western governments and statutory organisations, like the police, struggle to address cultural differences appropriately, even when those cultural differences quite clearly include highly exploitative and oppressive practices.

Fear of being culturally insensitive, or worse, called racist, is paralyzing to some people. I believe failing to challenge oppression is the most racist and misogynistic action a politician can take. To quote Desmond Tutu, “If you are neutral in situations of injustice, you have chosen the side of the oppressor.” In the U.K. one particular member of parliament, Lynn Featherstone, made tackling FGM her mission. The U.S. needs many more politicians willing to champion tackling FGM.

“It took almost thirty years from my first learning about FGM to actually feeling I had made a difference on behalf of the girls I once taught.”

AHA Foundation: You spent almost 30 years helping in humanitarian causes. What has been the most rewarding experience in this journey so far?

Lisa: There have been two key highlights for me personally: successfully lobbying for mandatory reporting in the U.K. and the British government agreeing to fund the National FGM Centre. It took almost thirty years from my first learning about FGM to actually feeling I had made a difference on behalf of the girls I once taught in Nigeria.

AHA Foundation: What about a time or experience where you felt disheartened?

Lisa: There is still so much work to be done, but if you want to know my most frustrating and disheartening experience, it was unsuccessfully spending two years lobbying the British government to make preaching in favor of FGM a hate crime against women.

We know many community leaders still falsely preach that FGM is a religious or cultural requirement, and yet there is nothing we can do in the U.K. to stop them unless it can be proved beyond a reasonable doubt that a child was subjected to FGM directly as a result of the preacher’s words. That’s too late for the child. Preaching in favor of mutilating a girl’s genitals is intended to provoke violence and should be regarded as a hate crime.

“FGM is closely related to fixed gender roles and perceptions of women and girls in terms of family honor, which in many cases is closely linked to strict expectations regarding women’s sexual ‘purity’ and lack of desire.”

AHA Foundation: In your experience, why do communities who still practice FGM have a hard time seeing it as child abuse, and condemning it?

Lisa: FGM is closely related to fixed gender roles and perceptions of women and girls in terms of family honor, which in many cases is closely linked to strict expectations regarding women’s sexual “purity” and lack of desire. By mutilating a girl’s genitals, it is hoped that she will have little or no interest in sex.

Many people from communities that practice FGM say that it is rooted in local culture and the tradition has been passed from one generation to another. Some people who support FGM justify it on grounds of hygiene and aesthetics, with notions that female genitalia are dirty and that a girl who has not undergone the procedure is unclean. There are no health benefits to FGM, only serious risks.

FGM is not particular to any religious faith, it is an interfaith issue of child abuse. It is erroneously linked to religion, yet it is not particular to any religious faith and predates all major religions. Some members of practicing communities inaccurately believe the practice is compulsory for followers of their religion. In the West, FGM is often misrepresented as linked with Islam, but this has been refuted by many Muslim scholars and theologians who say that FGM is not prescribed in the Quran and is contradictory to the teachings of Islam.

“FGM is not particular to any religious faith, it is an interfaith issue of child abuse.”

AHA Foundation: Have you worked with survivors of FGM?

Lisa: I have worked with survivors to raise awareness. These women are incredible, strong, and brave, but I am also aware that we must respect the rights of those who prefer not to be outspoken about their experience of FGM. It is a traumatic ordeal, and no one should be pushed into reliving their abuse.

I admire women like Layla Hussein and Ayaan Hirsi Ali. These women are exceptional in sharing their own, deeply personal experience in order to help others – they should be commended for it.

AHA Foundation: What is your advice to readers who would like to make a difference in the fight against FGM? How can they become involved and take action?

Lisa: It depends on where someone is living. If you’re in a state that hasn’t yet criminalized FGM, then I recommend writing your legislators. AHA Foundation can provide activists with model legislation, as well as details about the level of risk to women and girls in each state.

If someone is in a state that has criminalized FGM, then it is unlikely that the state has allocated a budget for education, training, or ensuring early intervention to help end the practice. Again, write your local representatives and ask for the appropriate resources to be allocated. AHA Foundation can help provide templates and details of the in-state risk to women and girls.

If someone doesn’t have time for lobbying, and it is a very busy world, then donations are always gratefully received by charities working to end FGM.

Finally, one thing we can all do is talk about FGM. Talk to your friends and neighbors, and help raise awareness of this practice.

AHA Foundation: What is your outlook on the anti-FGM movement? Do you think we will one day learn about FGM only in history books as a horrendous practice that existed in the past and is no longer threatening the lives of girls?

Lisa: That is certainly my aspiration. However, to reach the goal of eliminating the practice of FGM we need global cooperation, education, and understanding. At the moment politics is so polarized. This has sadly damaged the level of effective communication between governments and those who want to end FGM. Organizations that fund international development, such as the World Bank, should be doing more to leverage their strong negotiating position for the protection of women and girls. For example, international development funding of major infrastructure projects should be linked to governments taking appropriate action towards ending the practice of FGM.

The opinions stated above are the participant’s themselves and do not necessarily represent the views of the AHA Foundation.