“There is a very clear will to end FGM in the U.S., we just need the resources to finish it.” AHA Veteran Amanda Parker on 15 Years of the Fight Against FGM

Published 03/02/2022

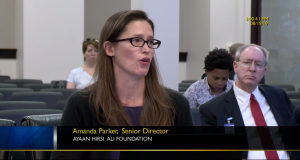

This year marks the 15th anniversary of Ayaan Hirsi Ali founding AHA Foundation. Since the very beginning, the Foundation has been focused on ending female genital mutilation (FGM), one of the most heinous crimes against women, in the U.S. For this blog, we spoke to Amanda Parker, Chief Financial Officer and Senior Director of AHA Foundation.

Amanda has been part of the team since very early on and is a veteran of the fight for women’s rights in the U.S. She has been on the frontlines of the battle to end FGM in the U.S. for nearly a decade and a half. In this blog, she speaks about the history of AHA Foundation, the highs and lows in the movement to end FGM in the U.S., and how she helped to build the Foundation into the national leader it is today.

AHA Foundation: Tell us a little bit about your background and how you became involved with AHA Foundation. Tell us about the first time you met Ayaan.

Amanda Parker: Prior to joining AHA Foundation, I worked on Wall Street, until the financial crisis of 2007-2008, when my entire division was shuttered. After taking time off and re-thinking my chosen career path, I was telling my dear friend Manon DeFelice (who would eventually become the Executive Director of AHA Foundation) that I was not planning to go back to the finance world. I was thinking of going into either publishing or nonprofit work because I could imagine wanting to get out of bed in the morning for either of those career paths.

Manon immediately thought of Ayaan, with whom she was friends, and connected the two of us. Ayaan needed help getting her office organized at the time, and we hit it off right away, so I started working for her almost immediately. I don’t remember many specifics from my first meeting with Ayaan, except that she came across as warm and gentle when I had expected her to be fierce and intimidating.

This was almost 13 and a half years ago. At that time, AHA Foundation was not the bustling and well-staffed organization you see today, just a group of generous individuals strategizing about how best to act on Ayaan’s vision while laying the bureaucratic groundwork necessary to make the Foundation a proper nonprofit.

AHA Foundation: What has your role been here—or roles, if it has changed?

Amanda Parker: Not long after the Foundation got seed funding and hired leadership, I moved from working directly for Ayaan to working for the Foundation instead. I started out as the Communications Director, but with an organization as small as ours (though we have certainly grown since those early days!), I have had my hand in everything from social media, to human resources, to IT support. Thankfully, I have shed most of those roles and, except for the time I’ve recently spent on maternity leave, I have spent recent years happily overseeing our women’s rights programs and handling the finances as the Foundation’s Chief Financial Officer and Senior Director.

When [Ayaan] came to the U.S. and saw that FGM was being practiced here as well, she was determined that it must end. She said that here in the U.S., we have the rule of law, resources, and social services, so there is no reason women and girls should be facing this form of oppression. … Ayaan was adamant that women and girls in the U.S. should be free from the persecutions she and her peers had faced growing up in Africa.

AHA Foundation: Why did Ayaan feel the need to set up an organization dedicated to fighting FGM in the U.S.?

Amanda Parker: Very soon after meeting Ayaan, I had the privilege to hear her speak publicly—frankly and courageously—about her own experience of undergoing FGM. I will always remember her highlighting that although she faced what to me at the time seemed like an unthinkable trauma, she is sadly not unique or exceptional in her experience. Although she knew the statistics of how many girls in her native Somalia had undergone FGM, she didn’t need those numbers because she knew from her childhood that it was a rite of passage that almost every female there would undergo.

When she came to the U.S. and saw that FGM was being practiced here as well, she was determined that it must end. She said that here in the U.S., we have the rule of law, resources, and social services, so there is no reason women and girls should be facing this form of oppression. Ayaan founded AHA Foundation, in part, with the vision of ending this practice here and supporting women and girls who had been impacted. Her vision regarding this facet of our work remains the same as it did at our inception—the U.S. must be a place where women and girls live with equality, free from facing the pain and subjugation of FGM.

AHA Foundation: As we mark our 15th anniversary year, how has the fight to end FGM in the U.S. changed since you became involved with it through AHA’s work?

Amanda Parker: Even before our first day of programmatic work, we were clear that ending FGM in the U.S. would be one of our biggest priorities. Ayaan was adamant that women and girls in the U.S. should be free from the persecutions she and her peers had faced growing up in Africa.

When we entered this fight, there were only 19 states that had enacted bans on FGM, and it was not yet illegal to take a girl overseas for the procedure. At AHA Foundation, we saw a huge need to hit the road and really tackle the problem of FGM across the U.S. on a state-by-state basis, first by encouraging legislators to ban the practice in every state, and then by ensuring that all professionals likely to encounter survivors or at-risk individuals were prepared to handle cases in a culturally-sensitive manner.

Amanda (center, seated) speaking at Penn State Dickinson Law’s 2018 conference ‘Crafting Legislative and Medical Solutions to Address Female Genital Mutilation Locally and Internationally.’

Although there was an existing national ban on the practice, we knew FGM was more likely to be handled at the state level, and there were large gaps that the federal government simply could not fill, including mandating education and outreach for professionals and communities and banning transporting girls across state lines for the procedure, among many others.

Crucially, we were also hearing from survivors that FGM bans send a strong message that the practice is not acceptable in the U.S., and that bans give them much-needed ammunition to fight back against family and community members who were pressuring them to have their daughters cut.

Although no other organization was working systematically to ban FGM across the U.S., there were a few large organizations doing excellent work in this fight, either on the national level or overseas, and there were some terrific local organizations serving the needs of survivors who lived nearby.

I’m proud to say that 15 years after AHA’s inception, there are no longer only 19 states but instead there are now 40 states that have in place anti-FGM legislation, and that’s not including the many states that have strengthened their existing laws thanks to our efforts. We didn’t have the capacity to work in every single one of those states that have passed laws since our inception, but we worked in most of them and our efforts certainly inspired others to take action. As a survivor-led organization with resounding success on the legislative front, thousands of professionals trained, and almost 15 years of expertise and experience under our belts, we are honored to be a national leader in this movement.

[O]ver time, I began understanding how FGM has negatively impacted many survivors, not just in the trauma of being cut, but in their day-to-day lives from there on out. I also got to know many survivors. This meant that FGM became something that has harmed people I know and care about: the fight became personal.

AHA Foundation: Why is this fight close to your heart?

Amanda Parker: When I first truly understood the mechanics of FGM, and that the perpetrators were often the mothers and grandmothers of the girls being cut, I was shocked and deeply upset. I had a visceral reaction and knew that working to end this practice was something I had to do. As the years have passed and I’ve spoken to more and more survivors, that conviction has deepened.

In the beginning, ending FGM in the U.S. was a necessary battle for the equality of all women. But over time, I began understanding how FGM has negatively impacted many survivors, not just in the trauma of being cut, but in their day-to-day lives from there on out. I also got to know many survivors. This meant that FGM became something that has harmed people I know and care about: the fight became personal.

AHA Foundation: How did survivors of FGM influence this movement?

Amanda Parker: From the very beginning, we’ve had survivors reach out to us to thank us for our work and express their admiration for Ayaan. They have also always reached out for practical support, seeking medical care or aid with an asylum application. We never set out to be an organization that worked directly with impacted individuals to help them find services, but because they came to us seeking help, and so few organizations were providing that type of support, we quickly realized that would be part of our work.

My most meaningful moments at AHA Foundation have all been when I’ve had the honor of working together with survivors, helping them face a difficult situation, joining forces to facilitate trainings or to push for anti-FGM laws. One moment that sticks with me followed months of working together with Jenny, a survivor and anti-FGM activist, to meet with Kentucky legislators and testify at numerous hearings where Jenny selflessly and courageously recounted over and again the trauma of being cut and the many ways undergoing FGM has harmed her health and everyday life.

During the final hearing for the bill, where committee members would unanimously send it on its way to eventually become Kentucky law—even though the building was on the verge of being shut down because of the pandemic and the hearing had run over time—legislators one after another took the time to thank Jenny for her testimony, some with tears in their eyes, sharing the impact her incredible generosity and vulnerability had made.

AHA Foundation: Tell us about the turning points over the last 15 years in the fight against FGM in the U.S.

Amanda Parker: Over the last 15 years, we have seen major shifts in the fight against FGM. The federal lawsuit against Jumana Nagarwala, a Michigan-based physician, for allegedly performing FGM on girls in a Livonia, Michigan clinic was one of the biggest. This case, which was unfortunately dismissed in 2018 due to constitutional concerns with the federal FGM law, was initiated following a whistle-blower coming to us at the Foundation, whom we connected with federal law enforcement.

Although AHA Foundation and other allies filed amicus curiae briefs in support of the prosecution and the federal anti-FGM law, the judge dismissed the case, calling FGM a “criminal assault” but ultimately determining that it “is a ‘local criminal activity’ which… is for the states to regulate, not Congress.”

This crushing ruling meant that the victims in this case would not see justice, but also put into doubt the ability to prosecute perpetrators using the federal law, leaving tens of thousands of women and girls living in states that, at the time, did not have anti-FGM laws vulnerable. The silver lining was that the significant media attention this case garnered raised awareness with the general public and, significantly, with state legislators. This led to an increased momentum bolstering our efforts to encourage state-level FGM bans.

At the end of 2019, we launched an ambitious campaign to ban FGM in 2020 in all 15 remaining states that, at that time, had not already banned FGM. It was shortly after that that the pandemic struck and put a serious dampener on those plans. I was in Kentucky to testify for the House Judiciary Committee the day the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a global pandemic. Within days, most state legislatures had shut down and/or rightly shifted their focus towards protecting their populations from the major health threat we all faced. Our momentum following the Nagarwala trial stalled. Almost two years later, we have yet to see all 50 states plus Washington, D.C. pass much-needed anti-FGM legislation, but we are now at a total of 40 states that have banned the abusive practice, a huge leap forward from when we started this work.

Does Your State Have An FGM Ban? Find out here.

A third turning point we were thrilled to see in the fight against FGM was when, in 2021, a law was passed affirming that FGM is illegal on the federal level when interstate commerce is involved. This may sound complicated but in reality, it means that almost all cases of FGM performed in the future in the U.S. would be illegal and punishable in a federal court. This new law addressed the concerns brought to light during the Nagarwala trial. Its successful passage was hugely gratifying—at AHA Foundation, we spent countless hours speaking with legislative contacts and strategic partners to ensure its passage.

The final milestone I will highlight is that the U.S. government very recently began providing federal funding specifically to combat FGM, which was not the case 15 years ago. One of the biggest challenges faced by advocates working to end FGM in the U.S. and to support survivors is a lack of resources needed to do so. The addition of federal funding helps alleviate that problem (though we need to see much more!) and signals that the U.S. government is serious about ending FGM.

At AHA Foundation, as 2021 came to a close, we were awarded a three-year grant from the Department of Justice to provide on-the-ground training to professionals likely to encounter girls at risk and survivors of FGM in Chicago North Side. We will use this critical funding to generate a support network, changing lives for an estimated 3,400 women and girls in the Chicago area.

Like most people, legislators often don’t know FGM is happening in the U.S., let alone in their state.

AHA Foundation: Can you tell us about the day to day aspect of the fight for state legislation? Did you have a grand strategy or did you tackle things one step at a time?

Amanda Parker: From very early on, we first researched which states had anti-FGM laws, then cross-referenced that with which states had the most women and girls at risk of or impacted by FGM. That gave us a priority list, which we added to over the years by researching which states had weak laws that also needed to be improved (spoiler alert—it was most of them!).

We haven’t always followed that roadmap, though—sometimes circumstances throw up opportunities that we can’t afford to miss. In one instance, a survivor eager to protect her daughters in her own state suddenly made a specific state our number one priority, even though that wasn’t according to our original plan.

We always seek out legislators who we believe would see the need to pass anti-FGM legislation in their state once they become aware of the issue. Like most people, legislators often don’t know FGM is happening in the U.S., let alone in their state. In many cases, raising the issue to sympathetic legislators and sharing data about its prevalence, and the fact that it causes lifelong harms, and that it is not mandated by any major religion, is enough to spur them to action.

That’s not always the case, though, and we’ve worked in some states for many years with dedicated coalitions comprised of survivors and other stakeholders before legislation is finally passed—this was the case in Massachusetts, and is the way we’ve been working in Connecticut, which has yet to pass much-needed legislation.

AHA Foundation: What does the future of the fight against FGM in the U.S. look like in your view? Are you optimistic?

Amanda Parker: Our work at AHA Foundation has been focused on introducing or changing anti-FGM laws as well as supporting survivors—the laws we urge legislators to pass and the trainings we lead for professionals do just that. We have made huge strides on the legislative front, but we’re not done yet, not until all 50 states and the District of Columbia have holistic laws protecting and supporting all girls in the U.S. from this human rights abuse.

As far as training goes, although we’ve trained thousands of professionals, we’ve barely scratched the surface. While we scale up our in-person trainings, we continue to seek innovative ways to ensure women and girls at risk are met with sensitive, appropriate care when they seek services, including our recently released online training on the American Medical Association’s platform, but so much more must be done.

But even this is not enough to end FGM in the U.S. Community-level work must happen to change hearts and minds across the nation. This work is already underway in some communities. Survivors, community leaders, religious leaders, men and boys, and other stakeholders must work together to ensure the equality of women and girls, and to educate people about the harms of this practice—that there are no health benefits, and the fact that it is not required by any major religion. That community-level work is an important path towards practicing communities turning away from FGM.

This is a battle we can win. There is a very clear will to end FGM in the U.S., we just need the resources to finish it.

The progress we’ve seen over the past 15 years and the passion I see in my fellow activists makes me incredibly optimistic. This is a battle we can win. There is a very clear will to end FGM in the U.S., we just need the resources to finish it.

AHA Foundation: We are going to share your blog with our supporters in a newsletter that will be sent on March 8, International Women’s Day. Now that you’ve recently become the mom of a girl, has it changed how you look at your involvement with women’s rights in the U.S.? Was that passion passed to you by somebody in your family?

Amanda Parker: I’ve always been one who gets a little frustrated when people say, “as the parent of a daughter, this is important to me,” because I believe that women’s rights should be important to everyone simply because we are all humans; we should care about the rights and dignity of fellow people, full stop. I still absolutely believe that. But after becoming the mom of a daughter, I look at her and I now understand why people say that. I have to fight for this world to be equal for this tiny human. The world I want for her is one where she is valued as she is, one where she is safe from persecution, one where her sisters both here in the U.S. and around the world are equally safe and valued.

I only realized it in hindsight, but my mom absolutely influenced my passion for women’s rights. Thinking back to my childhood, I have vivid memories of my mom talking to my second-grade teacher about how I would “break the glass ceiling” and that I would “get the Equal Rights Amendment passed.” I never thought of my mom as a feminist, but she certainly was. She imagined for me a home where I am equal under the eyes of the law and in practice. What my mom wanted for me is what I now fight for for my daughter.

AHA Foundation: What would you say to survivors and those at risk of FGM?

Amanda Parker: No matter how FGM impacts you, whether you’re a survivor needing a therapist or medical care, or trying to protect a girl in your family or community from being cut, support is available to you; please seek it out. We’re one of those avenues for help. Reach out to us at help@theahafoundation.org.