“We have to share the truth about FGM—the unnecessary pain and trauma it causes. We must help the voiceless to speak. We must educate.” Raha’s inspiring story of surviving FGM and becoming a champion for women’s rights.

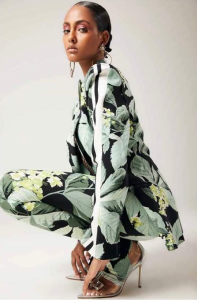

Raha Europ. Image credit: Nargis Magazine.

Published 10/3/2023

Raha Europ was born to Somalian parents in a Kenyan refugee camp, where she lived until coming to the U.S. at the age of 7. Growing up as a girl in her conservative community, she always felt she was treated unfairly compared to the boys. She thought female genital mutilation (FGM) was normal but her own experience of it and her later journey of understanding showed her that it was an unnecessary and abusive practice. Now, she is an activist and model who speaks up bravely against FGM and other injustices. This is her story.

AHA Foundation: Thanks for speaking with us today, Raha. Could you tell us about your background? Where did you grow up and how did you come to the U.S.?

Raha Europ: My family is Somalian but they fled the war there and I was born in a Kenyan refugee camp.

Alongside me were my two younger sisters and little brother. In the refugee camps, everyone shared the same beliefs and traditions. As a girl growing up, there was a lot of pressure on you—but not on the boys. And as the eldest child, I felt the most pressure.

The girls would cook and clean and the boys would have little to no responsibility. I didn’t have the opportunity to go to school in Kenya. I started in the third grade when I came to the U.S. aged 7. I didn’t experience serious culture shock when I arrived here—the U.S. isn’t all that different from the rest of the world. But one big difference stood out: in the U.S., many more people were willing to speak out against the gender-based injustices I had faced.

Within the community, however, it felt as if we were still in Somalia or Kenya. The traditions, the lifestyle, and the mindset remained with us.

AHA Foundation: Can you tell us more about how girls and boys were treated differently in your community?

Raha Europ: Growing up, I wasn’t taught about my body because it was shameful to speak about such things. Speaking about your period in front of men, even your own father, was unheard of. Everyone wore clothes covering them from head to toe. If you didn’t cover up, you were looked down on. It was a community where little girls were treated less than boys. I felt as if I had no voice.

There were so many differences in how boys and girls were treated. Girls were responsible for more things around the house. Girls were raised to feel ashamed of their bodies and to shame others. Girls were treated as full-grown adults before the age of 10. We didn’t get much of a normal childhood.

Seeing women treated so unfairly and so poorly, seeing them forced to live under a system where men were responsible for all the crucial decisions in their lives, made me feel like I had no autonomy. I felt that I was destined for a life of submission. But something in me, some spark of defiance, resisted that fate, though it would be a long time before that spark grew into a fire.

AHA Foundation: If you feel comfortable discussing it, could you tell us about FGM as practiced in your cultural community and your own experience of FGM?

Raha Europ: The perception of FGM within the Somali culture and community is that it is normal and expected. From the adult’s eyes, it is something that should happen and eventually will. And the children learn to expect it and think it will be a positive experience, one they can be proud of one day. Of course, most of them could not remotely know the truth of the experience, what it feels like.

“The last thing I remember is being tied up in a room, completely helpless… No pretty dress can make up for the pain and trauma of FGM.”

It is seen as something that makes you “clean” and “proper”. Going through the process of FGM was celebrated and expected in the community. If you weren’t cut, other girls wouldn’t play with you or wouldn’t want to be friends with you because you weren’t “clean”. If you weren’t cut, you would be seen as less “valuable” in terms of future marriage.

The day before it happens, you are treated very nicely. You are given your own party, you get a new dress. But the memories I have from this time are more of a nightmare. I was 6 when me and my sister were cut. I remember the experience so vividly. I remember this old woman showing up with a razor blade and nothing more. I remember the awful pain and nightmare of being tied up with rope all the way down to my feet. The pain was so extreme. I remember laying on the floor with a pool of blood near my body. Showing fear and crying was not an option; this was seen as a celebration rather than the nightmare it was.

No pretty dress can make up for the pain and trauma of FGM.

Knowing now that what was done to me was unnecessary and wrong makes it even more traumatic. It did not have to happen. It was a terrible injustice.

AHA Foundation: How did you come to realize that FGM was a human rights abuse?

Raha found her voice and decided to speak up against the injustice of FGM. Image credit: AFRO Style Magazine.

Raha Europ: I always viewed it as normal until one day in health class when I was 12 or 13. We were learning about the human body and for some reason it triggered my trauma. It finally clicked that FGM was an abusive and harmful practice, not a normal cultural ritual.

I went home and spoke to my mother and after a short discussion, all she could say was “I’m sorry”. After that, I went on a journey to understand what exactly had happened to me. This was the beginning of a long process of me refusing to be silenced any longer and finding my voice.

AHA Foundation: Tell us more about your journey of understanding and how you found your voice.

Raha Europ: Even when I was little, I questioned everything. Why did a woman have to be cut in order for her to be worthy of her husband? Why were women and girls treated so differently? Was this really how things were meant to be? It all seemed so unfair from a woman’s perspective. So many things were not equal. I didn’t agree with a lot of things like young girls being sent away to be married. Don’t question things, play the part your family and community want you to play rather than being who you truly are—that was the message all girls received. And I didn’t like it one bit, even though I felt I had to go along with it.

After my discovery in health class and my journey of understanding, I realized that things did not have to be this way. When I saw photos of what FGM did to other women, I felt the pain all over again. I remember how painful it was for me to pee. I knew then that FGM and gender inequality were injustices to be fought, not facts of life to be endured. And I knew that there were people within my community who also questioned these ideas, but stayed silent for fear of being ostracized. I could not remain silent, though. I decided to speak up.

I spoke up because I remembered all those moments where I felt that I never had a voice. I spoke up for all of those women and girls who can’t yet speak up. It’s for all of them as much as it is for me.

AHA Foundation: Were you surprised to find that FGM happened in the U.S., too?

Raha Europ: I was not too surprised. Certain cultures, regardless of where they may choose to live, bring certain aspects of their culture and identity with them. In many cultures, FGM is something that is seen as normal. For many in the U.S., however, FGM isn’t spoken about in the community as much as it is back home. Talk about FGM is more hushed in the U.S.—almost as if people know it is bad even as they still continue the practice.

AHA Foundation: Could you tell us about your anti-FGM activism and future plans?

Raha Europ: I hope that I can be a voice for myself and others while I find my way to get my power back. I would like to be able to help little girls have a safe space to grow and speak and be themselves, so that they can discover the power in their individuality. I want to aid the global effort to educate people on the harms of FGM.

“If I can connect enough dots to prevent even just one little girl from going through the traumatic experience of FGM and help her to lead a life of her own, then I will know I am on the right path.”

By uniting those who are against FGM and who are willing to speak out, our many voices can become one loud voice that is impossible to ignore. I am currently creating a non-profit that will reach out to the community to foster those relationships and establish a voice within the community for change. If I can connect enough dots to prevent even just one little girl from going through the traumatic experience of FGM and help her to lead a life of her own, then I will know I am on the right path.

AHA Foundation: How can our readers support you in your mission to end FGM?

Raha Europ: The best way for readers to support the mission to end FGM is to educate themselves on the topic and discuss it with the people around them. Every woman should be empowered to use their voice to call out injustice. For anyone who has been affected by FGM or knows someone who has, I hope my non-profit will be able to support them. For anyone wanting to connect, please reach out to WomanOnWinning@gmail.com, and let’s start a dialogue. You can also connect with me on Instagram here.

There is nowhere near enough discussion about FGM. We need to change that.

We have to share the truth about FGM—the unnecessary pain and trauma it causes. We must help the voiceless to speak. We must educate.

It’s very difficult to champion change when you are unaware of the injustices you are accustomed to. Growing up I didn’t have a support system or a means of finding others to speak to. Knowing where to find knowledge and support is crucial in the fight against FGM.

AHA Foundation: Are you hopeful about the future? Do you think we can ever end FGM?

Raha Europ: The future is bright. I can see more women being empowered to speak the truth about FGM. I can see more women being aware of the injustices surrounding them. More women are now choosing to decide they have a voice, which is very important. The more who speak up on things like FGM and child/forced marriage, the better our chances of ending these injustices forever.

The young women choosing to stand up and call for change inspire me. I think they will make the future a brighter place. It will require a lot from everyone but I am hopeful that we can end FGM. I know there is hope because I was once someone who knew nothing and who didn’t have a voice. Change is possible. Women who stand up and embrace their power and their voice will inspire even more women to join them. As I said earlier, in places like the U.S. we have much more freedom to use our voices, so we must take responsibility and speak up for the many women who are less fortunate.

When I saw strong women who looked like me—people like Ayaan Hirsi Ali, Waris Dirie, and Hibo Wardere—I felt inspired to speak up. They motivated me to speak my truth without caring what others thought of them. These strong women gave me hope and courage that I didn’t know existed within me. I can only hope to have the same effect on other young women and little girls everywhere looking to find their voice.