“Girls have a right to thrive in the life they want for themselves. Not what someone else forcefully imprints on them.” Sasha K. Taylor Survived Child Marriage in the U.S. – Now She Fights Tirelessly to End It – Part 1

Published 03/02/2022

When team members from AHA Foundation spoke to Sasha K. Taylor, we were immediately moved by the strength of her passion, dedication, bravery, and commitment in the fight against child marriage in the U.S. A survivor of child marriage herself, she emerged out of this horrific experience resolute in her vision to protect children from what she endured. She is a true warrior for the rights of women and girls. We are honored to share the first part of her story with you today.

My name is Sasha K. Taylor. I am ethnically Pashtun, born in Karachi, Pakistan, and raised in Arizona. When I was 15 years old, my family forced me into a child marriage to a man who was seven years older than me. I became the latest victim in a cycle of abuse going back generations: my grandmother was married in a refugee camp at age 8 in Karachi after the Partition between India and Pakistan.

It has been many years since I went through the hell of child marriage but I started to tell my story only a few years ago. I hope you will read my blog and be inspired to join the fight to stop child marriage in the U.S.

The day my life changed forever

On the day my life changed forever, I came home from school and got off the school bus—it was just a normal day. And then I encountered my grandmother, who lived two houses down from me. She told me there was a dinner party taking place that night and to come over. I went and found many people attending from the desi [of the Indian subcontinent] diaspora. After dinner, a chair was placed in the center of the living room and I was told to sit.

A woman I had never seen or met before walked up to me and placed a gold chain around my neck. As she was doing that, she asked if this was okay with me.

I kept wondering aloud, if what was okay with me?

I looked up at my grandmother and mother, who were standing on either side of me, and I asked them what was happening. They both glared down at me and told me to be quiet. I looked down at the ground. And at that exact moment, everyone started hugging each other and congratulating each other.

That was the moment I realized I had been forcefully engaged to a man I had never met. He was seven years older than me. After the forced engagement I found out his student visa was expiring. I was taken out of school for a day, dressed up in clothes meant for a mature woman, made to put a lot of make-up on my face, and we were legally married in a local courthouse. After, I was used as his visa sponsor.

The day I fell silent

I spent my entire high school years legally married. My family was told that my husband’s family would pay for my college, but that never happened. Instead, my family took out student loans and signed me up for college classes a week before the start of school.

When I started at Arizona State University (ASU), I saw the possibility of a life I could have for myself on my own terms. I had already been telling my family I didn’t want the forced marriage—yet I kept referring to it as an “engagement” because to me the legal part of the court marriage didn’t matter. It didn’t matter to my family either because we had not had our nikah (religious marriage ceremony) yet. The lines between what the state legally considers marriage and what the community culturally considers marriage are not one and the same.

The nikah happened in a mosque in front of the Muslim community attending evening prayers. They were witnesses to my forced nikah. I was told that people were aware that what was happening was forced.

They heard me cry. They heard my silence. They watched in silence as I was forced into a nikah with a man I did not want to marry, a man I had no feelings for or sexual attraction toward.

On that exact day, in that exact moment, I fell silent. I fell numb.

I told my family I wanted out, but they kept telling me that they had given their word, and whether I divorced him or not the next day after my nikah was up to me. The entire burden of getting out of a situation they had forced me into was on me. I was eventually also forced into a nikah with this man. I was not given a choice in any of these matters.

The nikah happened in a mosque in front of the Muslim community attending evening prayers. They were witnesses to my forced nikah. I was told that people were aware that what was happening was forced.

They heard me cry. They heard my silence. They watched in silence as I was forced into a nikah with a man I did not want to marry, a man I had no feelings for or sexual attraction toward.

On that exact day, in that exact moment, I fell silent. I fell numb.

I was not allowed to leave my husband’s family home after the nikah unless I was going with him. I complied. I went to school and then would come back to their home. I did not know what to do, so I would just pace their home. I was a prisoner in their home. I was a hostage.

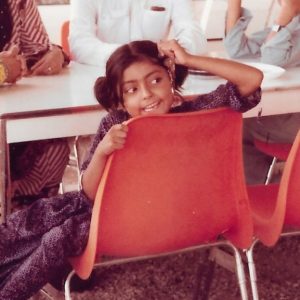

Sasha at the courthouse for her marriage. Sasha’s outfit was bought from the older women’s section of a store by her husband’s parents.

I started leaving school and going to see my mother. It was the only way I found to spend time with my family. I felt completely isolated from everyone around me. Going back to see my mother was the only consolation I found. I ended up flunking out of ASU after one semester because I had stopped attending classes.

Escaping forced marriage was not enough—but I broke free in the end

My mother became ill and so I finally found a chance to escape. I told my husband and his family that I wanted to spend time with her. My mother-in-law told me I couldn’t go for the weekend, but I could go during the day and come back at night. That was my chance. I grabbed my car keys and purse and walked out the door. I ran and never went back. By this time, and because of their actions, my family was supportive of my decision to leave. Thankfully, my family had realized what a horrible mistake they had made.

But that was short-lived.

My mother and I went through a divorce at the same time, both putting an end to abusive relationships that we had been forced into. My mother remarried. However, even after leaving my forced marriage, and knowing the catastrophic situation I had just escaped from, and understanding my desire not to be in a similar situation again, my family kept pushing me into other forced proposals and attempted marriages. It was relentless. I was always someone they had to ‘give away.’

I even found my own advertisement in the local Muslim community newspaper. It made me feel like I was cattle at the auction ready for sale. It was so degrading and dehumanizing. It was a constant reminder that I was not wanted by my own family. But I refused to give in to the pressure: I would not be defined in this way. I would define myself. I would break the cycle of abuse that began with my grandmother all those years ago during the Partition.

The entirety of these traumatic events set me back over 10 years in my education. I always wanted to finish my education, so I started classes again at Mesa Community College, then I finally earned my bachelor’s degree in Education at Arizona State University, and then went on to obtain a master’s degree in Broadcast Journalism from Michigan State University.

After leaving Michigan, I knew I could never go back to Arizona or to my family because of the possibility that I would be coerced or forced into another unwanted marriage. I kept moving forward and moved to Washington, D.C., even though I did not have a job or an apartment lined up. I stayed on a friend’s couch while I looked for jobs and a place to live.

My first apartment was on Capitol Hill, and I started temping in D.C. After four years of this, I finally found a job at the Federal Bureau of Investigation and worked there for a little over 11 years.

Why I had to speak out

I had just parted with the Bureau when Afghanistan fell. I read news of child marriage being used to secure U.S. visas as a gateway into the country and I realized that nothing had changed since I was victimized by my family and the U.S. legal system 30 years ago.

[Child marriage in the U.S.] is an issue that state lawmakers and Congress are not acting fast enough to fix. It is an issue that needs immediate attention to protect girls from being exploited by their own families, families who still think of their children as a commodity to offload in difficult economic times…

I also realized that any refugee minors entering the United States may fall victim to archaic laws and loopholes if their families try to marry them off. That is why I have chosen to use my voice.

I want to raise awareness about this critical issue and to advocate for the refugee and immigrant minors entering the United States. I also want to advocate on behalf of all the South Asian women whose lives and opportunities have been destroyed by their own families’ exploitation of loopholes to marry them off as children. This is an issue that state lawmakers and Congress are not acting fast enough to fix.

It is an issue that needs immediate attention to protect girls from being exploited by their own families, families who still think of their children as a commodity to offload in difficult economic times, with marriage as the means to do so, instead of creating healthier patterns like seeking out the many social resources available to uplift them out of difficult situations.

I started my official activism work against child marriage in late 2019. However, my own writing on this matter goes back even further. In 2007 I started writing a book to analyze the historic issues within my own family that led to all the paths taken. In writing this book, patterns began to emerge within the cyclical behaviors of my mother, grandmother, and myself and how they related to our own forced child marriages and the domestic violence we all suffered in our lives. I planned to use the proceeds from this book to start a fund for girls escaping child marriage in the U.S.

It was also during this time that I realized I needed to connect with a a non-profit working to end child marriage, so I reached out to the Tahirih Justice Center. With their help, I testified in Maryland for a bill to ban child marriages for anyone under the age of 17. Preferably, that age would be 18, but 17 is a good start in my view. The current marriage age of 15 makes Maryland a prime destination for trafficking.

I wrote a victim impact statement about my own personal experience and what it was like to be forced into a child marriage and not have a voice in this life-changing decision. It was an incredibly difficult moment to be up there testifying and watching everyone look at me as I experienced my first ever anxiety attack and breakdown—on camera.

All too often, the issue of child marriage becomes abstract, spoken about in an impersonal, detached manner. This masks the pain and suffering of victims and survivors, whose stories should be front and center. It is also troubling that women are conditioned to be passive, to put up with abuse in the name of tradition—”that’s just how it is.” This is how I was conditioned by my own family. Even at the FBI, I self-regulated. And even now, years after my escape, I sometimes feel ashamed and fear I won’t be taken seriously if I don’t talk about my trauma in calm, polite tones.

But I don’t let that stop me from speaking my truth: I have learned to become comfortable in my own skin and I refuse to conform to anyone’s expectations of me. As far as I’m concerned, I do not owe anyone any part of myself or my emotions anymore. No woman should feel that way.

I try to sprinkle the uncomfortable topic of child marriage in almost every conversation I have with people who are not aware of this issue. Now it comes up naturally because people I encounter ask what I am doing and I tell them I’m fighting child marriage, and I tell them about all the amazing non-profit, non-governmental organizations I’m partnering with and all the work we are doing.

The Department of Homeland Security needs to have an active campaign on the child marriage issue since they see it all the time in visa applications. … At the end of the day, government organizations care about things Congress is telling them to care about, or what things Congress is throwing money at them to care about. And I can tell you, child marriage is not one of them. This must change.

I recently brought it up to the school principal at a meeting. She had no clue child marriage was even an issue in this country. The U.S. Department of Education needs to engage on this topic immediately since it affects so many minors across the country. If they have curriculums providing education on puberty and development then they need to add child marriage prevention to their roster and train school counselors from K-12 about this issue.

The Department of Homeland Security needs to have an active campaign on the child marriage issue since they see it all the time in visa applications. All that shows me is that someone there hasn’t made it a priority to write to inform their leadership that this is an issue, or that they just don’t care, or that they do care but also know that Congress won’t throw money at them for it so they don’t even give it the time of day.

At the end of the day, government organizations care about things Congress is telling them to care about, or what things Congress is throwing money at them to care about. And I can tell you, child marriage is not one of them. This must change.

I started an advocacy and media firm named Reality of a Desi Girl™ after news stories started emerging about the Afghan refugee crisis. I began partnering with non-profit organizations across the U.S. that are seeking to reform outdated marriage laws and immigration policies that allow for the exploitation of minors.

But my work has only just begun.

In next month’s blog, Sasha will share what she is doing to end child marriage in the U.S. and how others can help in this fight.

Find Out More About Sasha and Her Fight

- Visit the website of Sasha’s advocacy and media firm Reality of a Desi Girl™.

- Sasha’s story was featured on WUSA-9, including her Maryland victim impact testimony.

- Sasha’s opinion piece for The Washington Post on the importance of raising the legal marriage age, reforming immigration laws, and passing a U.S. Federal Marriage Law.

- Sasha’s appearance on The Washington Post podcast Please, Go On with James Hohmann to discuss her opinion piece.