The Toll of Female Genital Mutilation Through the Eyes of an Award-Winning Photographer and FGM Survivor

03/24/2021

Discussing female genital mutilation (FGM) and seeing visuals that depict the practice can be uncomfortable for many people, but both are necessary if we want more people to become aware of the fact that this gender-based violence is happening behind closed doors. Through her photo collection depicting the horrors of this practice, Egyptian photographer and FGM survivor Somaya Abdelrahman humanizes the practice of FGM and highlights how it affects girls’ everyday lives.

Somaya Abdelrahman knows the toll that female genital mutilation (FGM) takes on a girl’s life firsthand. After suffering through the years of silence, pain, and trauma that come with this dangerous practice, Abdelrahman vowed to help other survivors speak their truth and break the silence that keeps FGM hidden from the public eye.

Through her award-winning photo collection, she has brought attention to the atrocity of FGM. In her blog below, she tells us about her personal story, the inspiration for her work, and the goals behind her advocacy.

By Somaya Abdelrahman

It is safe to say that the day I underwent female genital mutilation was by far the worst day of my life.

I grew up in a country that is infamous for the highest rate of FGM in the region—Egypt. Although a 2008 law was enacted criminalizing FGM, Egyptians still consider it as one of the most important religious and traditional rituals. The community and specifically families force their own rules on girls, believing that it protects the female’s dignity and honor.

According to governmental documents, approximately 90% of women in Egypt under the age of 50 are circumcised. It is a discriminatory practice that attempts to control women’s sexual lives. The number of girls who die from circumcision is unknown because deaths are recorded as a result of bleeding or an allergic reaction to penicillin.

I feel for every other girl or woman that had to undergo this.

I was circumcised at the age of 10 at my friend Shayma’s house. A man who we were told was a doctor gave me three injections and then took my clitoris. It was a group mutilation event, there was a lot of screaming. I don’t remember much, but I was disfigured. I was a child at that time, I did not know how to behave, but when I grew up I went to a doctor so that I could fix what happened to me.

I have always been very concerned about women’s rights and gender equality. This passion and concern was what kindled me to produce documentary work that brings this crime to light. For me, projecting a story visually through photography offers a medium to expose the ugly truth, to tell a story, or to spotlight underrepresented groups of people. I want to protect every girl who could be circumcised and protect her from this painful experience, which is an outright violation of women’s rights.

I started working on my photo project in 2018. I was hoping that it would reach the Egyptian society that reveres customs and traditions and does not care about the psychological and physical health of girls. I also hoped that it would be published on a global scale so that it would reach organizations and show what is happening to girls in Egypt so that they could help influence the public opinion in Egypt to make the laws more stringent.

I think that starting the discussion is a very good step so that I can show how horrible female genital mutilation really is.

I think I achieved part of that goal, as my photographs were published on many local and international news platforms. I received many positive and negative reactions and was able to start a conversation with those who support my fight. It hasn’t made a huge impact yet, but I think that starting the discussion is a very good step so that I can show how horrible female genital mutilation really is.

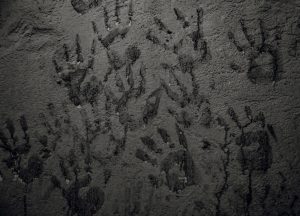

The photo that I am sharing (which can be seen at the top of the blog) with AHA Foundation’s supporters I think captures this best. I like this photo more than others because it shows the items used during circumcision—a blade and ashes. This woman performs the cutting with a razor and ashes are used to help heal the wound. Many people can not believe that FGM is still practiced, especially not with these tools—as if we were living in ancient times.

I firmly believe that visuals could bolster a cause, and this is my means to engage creatively with human rights and social justice issues. Documentary photography is certainly one way to address these issues, at least to start a conversation, raise awareness and improve education on female genital mutilation.

A week later, my place of residence was stormed by Egypt’s National Security several times. It was at that time I decided to leave Egypt.

Before I started on this project, I used to work with many news sites and channels in Egypt, writing articles about forced evictions and displacement. Last September, as I prepared to board my first-ever plane journey to Beirut to attend a workshop about documentary photography, I was stopped at the airport and was prevented from traveling. They took my passport, all because of my writings.

A week later, my place of residence was stormed by Egypt’s National Security several times. It was at that time I decided to leave Egypt. The situation in Egypt had become so dangerous for all Egyptians, especially journalists. Since the outbreak of the January 25 revolution, Egyptian women have participated in record numbers in various displays of expression of opinion, and as a result, they have been subjected to tribulations ranging from harassment, arrest, injury, or death.

Ever since President Abdel Fattah Al-Sisi became the Egyptian president in 2010, women have suffered from arrest, torture, enforced disappearance, murder, and even rape because of their own or their relatives’ opposition to the regime. According to the legal status report for the year 2018 issued by the Al-Shehab Foundation for Human Rights, women in Egypt have suffered from numerous violations, as they were subjected to arbitrary detention, imprisonment, humiliation, and harassment in detention centers, as well as denial of food or medicine. Some of them were sentenced to jail for up to 5 years because of their opinions, kinship, lineage, or human rights activities.

More on FGM:

- The 11 States That Risk Becoming Destinations for Performing FGM

- What is Female Genital Mutilation (FGM)?

Through my documentary work, I express what women and girls are going through and cannot openly talk about. I give them an avenue to discuss the most difficult subject of their life. My photo project provides stories for these women who can’t tell their own, whether they have been subjected to detention and have been released or are still in detention. But it is also an avenue that enables me to share my experience. It could be my attempt to reduce the trauma I went through and also a strong desire to protect every girl who could be exposed to this cruel experience.

But even through all of this hardship, I believe women can make a difference in the future. My thoughts go out to every lady who suffered FGM or other abuse and violence. I would like to tell them that we are strong and that I hope that they talk about their experiences and do not feel ashamed to seek medical professionals. I’d also encourage them to protect their daughters and relatives from circumcision. Together, we can help show the world just how awful this practice is and support each other through healing.

You can see Somaya’s entire photo collection here.

There are the writings of Somaya Abdelrahman and do not necessarily represent the opinions of AHA Foundation.