AHA Fellow on Hosting Campus Events Despite Protests and Pushback

Mohamed Ali is a sophomore at the University of Rochester studying physics and philosophy. He joined the Critical Thinking Fellowship, AHA Foundation’s campus program, in 2018.

AHA Foundation: How did you become a fellow in the Critical Thinking Fellowship (CTF)? What made you want to join the program and become a fellow?

Mohamed: All of my heroes, both past and present, are free thinkers who challenged the orthodoxies of their time. I hoped to find an opportunity to engage in the same activism as them.

Some of them are ex-Muslim public figures and Muslim reformers who are passionate advocates of ideas that I take seriously. Both Ayaan Hirsi Ali and Faisal Saeed Al Mutar are on that list. So when Faisal posted on his Facebook page that he was looking for college students to join a fellowship program, I immediately jumped on the opportunity.

“I think too many people are either unaware of, or purposely ignore, the real connections between extreme religious beliefs and terrorist groups, so I thought it would be a good idea to host an event specifically on this topic.”

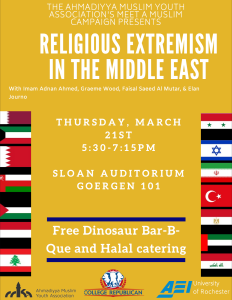

AHA Foundation: You recently hosted the event “Religious Extremism in the Middle East” at the University of Rochester. Can you tell us about the push back you received prior to the event?

Mohamed: The event focused on the link between religious beliefs and extremist groups in the Middle East like the Islamic State and Al-Qaeda. I think too many people are either unaware of, or purposely ignore, the real connections between extreme religious beliefs and terrorist groups, so I thought it would be a good idea to host an event specifically on this topic. The event was scheduled in late March: a week prior, a white supremacist terrorist massacred innocent Muslims in New Zealand.

This atrocity gave a reason for the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) to petition to cancel the event, although they had already opposed it before the attack. SDS, the Arab Students Association, and the Muslim Students Association disapproved of the event and said events like ours promoted the sort of anti-Muslim bigotry that motivates white supremacists. This is a common criticism by those who are either unable or unwilling to make a distinction between individual Muslims, Islam, and the dangerous political ideology of Islamism.

It is also the sort of criticism made by those who want to pretend that Islamism is not a real phenomenon, and this sort of denial allows repressive ideas to go unchallenged both in the West and in the Middle East. If the protesters’ real concern was the well being of Middle Easterners, they would have recognized this.

“…but uncomfortable conversations are necessary if we want to improve the world”

AHA Foundation: Did you anticipate the push back you received?

AHA Foundation: Did you anticipate the push back you received?

Mohamed: I anticipated push back; I knew very well that broaching the topic of how religious beliefs can motivate violence would make many people uncomfortable. Indeed, it made me uncomfortable when I first considered it, but uncomfortable conversations are necessary if we want to improve the world. Any successful cultural movement will undoubtedly make some people uncomfortable. The purpose of an event should not be to stir controversy for its own sake, but some push back is to be expected. That being said, I was surprised by the extent of the hysteria that would manifest itself on the part of some protestors.

AHA Foundation: Can you tell us about the question and answer session where protesters hijacked the session?

Mohamed: Question and answer sessions present a valuable opportunity to have the audience challenge the speakers, and push them to elaborate or clarify their points. When done correctly, the additional dialogue has the potential to change many minds. But for this to occur, a certain etiquette has to be observed— audience members should not heckle, interrupt, or try to hijack the session. Some of the students attending our event did just that, and in doing so they crowded out other audience members who had something valuable to say.

There was a student in the audience who wished to challenge the speakers on a certain point — but he was not allowed to because other students did not respect time limits and would not leave the microphone when requested.

AHA Foundation: You did a great job moderating this contentious discussion and holding the engaged parties accountable to exchanging ideas and feedback in a civil manner. How did you manage that process, and what helped you keep your focus amidst the heightened emotions you were surrounded by?

Mohamed: I think in situations like that, it is very important to keep in mind why what you’re doing is important to you. Hosting an event on controversial topics can either be an uplifting experience where you feel like you are helping spread a very important message — like it was for me — or it can feel like a burden that adds stress to an already busy semester.

I was constantly aware of why the topic of the event mattered to me, and so when difficulties arose I still kept my focus. You also have to remind yourself that a lot of people do want you to succeed like AHA Foundation’s Campus Program Coordinator, Julia O’Donnell, and our talented speakers who travel distances and made time for me and my event. They were rooting for me, and their support helped me tremendously.

As far as moderating the conversation, my goal was just to ask each panelist clear questions that prompted them to explain clearly what their view was on the topic of Islam and terrorism, and I would follow up by asking the panelists that disagreed to elaborate on their objection. I approached the discussion with the mindset of, “what would someone new to this topic want to know?”

“What is the point of holding events at all if their terms are set by those who don’t want to address the issues you are concerned about?”

AHA Foundation: After hosting an event that turned out to be controversial, what did you learn from this process?

Mohamed: One important lesson is not to quell the controversy by misrepresenting the event. Someone who was planning the event with me tried to underemphasize the fact that the event would tackle the thorny issue of how Islamism plays a central role in the way terrorist groups shape their goals and operate.

Doing this backfired, because it appeared to people that the event was fallaciously advertised. In general, amending an event that deals honestly with a topic to satisfy those pressuring you to cancel it is a bad idea; even if you succeed in quieting them, this is only a Pyrrhic victory. What is the point of holding events at all if their terms are set by those who don’t want to address the issues you are concerned about? Thankfully, the actual content of the discussion portion of the event was in my control, and I managed to go through with it as planned without such external influence.

“The sort of people you want at the event are thoughtful individuals who may or may not agree with you, and they want to be engaged on a deeper level than mere controversy – they want to understand, and it’s your responsibility as an activist to help them.”

AHA Foundation: What advice do you have for other CTF fellows, and advocates in general, who want to promote dialogue around controversial topics like this?

Mohamed: If you think that you are being practical by misrepresenting your event so as to bypass on-campus objections, please think again: it doesn’t work.

I would also tell any CTF fellow that the controversy is not the point of the event. The point is to help the audience grasp the facts you’re trying to deliver. The sort of people you want at the event are thoughtful individuals who may or may not agree with you and who want to be engaged on a deeper level than mere controversy – they want to understand, and it’s your responsibility as an activist to help them.

“Racial exclusion is when someone who objects to your views questions your authenticity as a member of an ethnic group.”

AHA Foundation: You wrote an article published in Quillette, an online magazine about science, technology, news, culture, and politics, about your event and a term you coined “racial exclusion.” Can you explain what “racial exclusion” means and how you experienced it at the event?

AHA Foundation: You wrote an article published in Quillette, an online magazine about science, technology, news, culture, and politics, about your event and a term you coined “racial exclusion.” Can you explain what “racial exclusion” means and how you experienced it at the event?

Mohamed: Racial exclusion is when someone who objects to your views questions your authenticity as a member of an ethnic group. The sort of criticisms that Faisal and I got at the event was that we were betraying Arab-kind by discussing Islamism. This sort of view implies that to be an Arab means to live your life according to some script which determines for you the sorts of beliefs you should hold.

It’s an attempt to bypass my ability to think about and choose the ideas that matter to me by conflating the unchosen aspects about me — my race — with the chosen — my beliefs about a certain topic.

To such people who practice racial exclusion I would say: “If you think my ideas are unjust and harm a specific group of people, then the burden of proof is on you to show me how they do so and to elaborate in clear terms where I am mistaken, but don’t accuse me of violating some sort of racial social contract that I never signed on to.”

The opinions stated above are the participants themselves and do not necessarily represent the views of the AHA Foundation.